- An empty parking lot

- A parking lot full of out-of-state cars

- A billboard promoting the salad bar

- An aged HELP WANTED sign in the window

- A video game instead of a jukebox

- A "microwave oven in use" notice

- A menu that tries to be cute or artistic, instead of straightforward and legible

- Nametags on the waitresses

- No toothpicks near the cash register

- Watery ketchup in the bottle

- Pickups in the parking lot

- Police cars in the parking lot

- Softball trophies behind the counter

- A view into the kitchen through the order window

- A separate handwritten and photocopied note on the menu with the day's special

- A list of the pies available, written with chalk on a slate

- A lot of calendars

- Older, rather than younger, waitresses

- The first dollar bill the cafe earned, in a frame on the wall behind the cash register

- A big clock with rotating advertisements for local insurance agencies, banks, hair stylists, and auto body shops

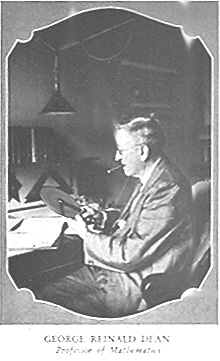

``Yes sir, there's just three kinds of time around this institution - bell time, whistle time, and in Calculus we have a hell of a time!'' __attributed to George R. Dean, in the 1926 Rollamo

"The universal language of the future, in the view of the tiny minority who now use it for their lives, will be mathematics. It could be so. Certainly, no other human endeavor can present so powerful an argument for a long survival in the centuries ahead, nor so solid a case for having already influenced and changed, largely for the better, the human condition. Among the sciences, mathematics has advanced more rapidly and at the same time penetrated the human mind more profoundly than any other field. I would include, most conspicuously, physics, for all the showiness of its accomplishments, and even cosmophysics; these disciplines would still be studying Galileo were it not for events that have happened in just the last three centuries in pure mathematics." __ Lewis Thomas, Et Cetera, Et Cetera, p.161.

"Ordinary language can be taken as a biological given; we are born with centers and circuits for making words and stringing them along in sentences that make sense to any listener. Mathematics is quite something else, not in our genes, not waiting in the wings of our minds for the proper time to begin speaking numbers. Numbers, their symbols and the ways of manipulating them into the outer spaces of abstraction have to be worked at, learned. To be sure, our sort of species has long required an agility with numbers for its plans to succeed and make progress as a social species, but meeting this imperative is not a gift we come by automatically, as we do with speech. The Indo European root for "mathematics', prophesying the whole future of the enterprise, was mendh, meaning learn. Not a root suggesting something natural, lying around in the world waiting to be picked up. On the contrary, a new, ungiven human activity, requiring lots of hard thought and hard work, even possibly, at the end of the day, unattainable. But mendh, learning something, also implies something peculiarly pleasurable for the human mind, with cognates carrying the meaning of awake, alert, wise, and eager." __ Lewis Thomas in Et Cetera, Et Cetera

``Criticism of science that I hear comes from people who have really maade no attempt to grapple with it. So I think of [sic] little of it as I think of Jeremy Bentham's disdain for poetry, since I know that, though he was a great man, he did not understand what poetry is about. If a man criticizes science, and it turns out that he does not know a quantum from a quantifier, I am bound to say, `When your guru has taught you how to solve linear differential equations, I will listen to you.' I am sorry if that sounds high-handed. But man did not get where he is by cutting out the hard intellectual work, and drawing his judgments from the pit of his stomach.'' __ J. Bronowski, from an interview in American Scholar

``The rarefied atmosphere of abstract thought is not an outer space reserved for professional mathematicians. If you have learned to add two and five without asking `Two and five what?' you already have both feet off the ground. The rest is just a matter of gaining altitude.'' __from Gateway to the Great Books - Mathematics

``... let me plead ... for the highest consideration to be given to the pursuit of pure knowledge as well as technical training, not neglecting mathematics, once called the Queen of the Sciences. The wind bloweth where it listeth, and the spirit of knowlwdge does not follow the quest for wealth and power; but the creation of new knowledge makes for the high repute of a nation, alike in the days when its influence is dominant and more in the distant days when its doings shall have been recorded on the scroll of time.'' __A. R. Forsyth, Mathematics in life and thought, Gateway to the Great Books - Mathematics

``The preoccupation with acquiring Prestige, once embraced at the highest administrative levels, gets trumpeted far and wide on the wings of magnificent rhetoric as a commendable, even noble pursuit. The party line trickles down through deans and department heads. Professors, wanting to eat, are quick to take the hint: Bring in that grant money and crank out those research papers. Or leave.... One casualty is today's students. Don't blame them for their overly job-centered attitudes. They soak up what they see... Another casualty is the overwhelming flood of marginal technical scholarship... Quality is out and quantity is in. Slice the baloney as thin as you can. Remember, the reward system is that numbers game: What matters is how many publications you get out the door. This paper pollution also winds up choking the very peer-review system that is supposed to pass judgment on the merit of research papewrs submitted to professional journals. ... for the Prestige focused university, the place of research has been inflated far out of proportion to less glamorous or less revenue-generating tasks.'' __Edwin M. Young in Notre Dame Magazine, Winter 1987-88

``When ... you go out into the `battle of life', you will be confronted by an organized conspiracy which will try to make you believe that the world is governed by the idea of wealth for wealth's sake, and that all means which lead to the accumulation of that wealth are, if not laudable, at least expedient. Those of you who have fitly imbibed the spirit of our University ... will violently resent that thought, but you will live and eat and move and have your being in a world dominated by that thought. Some of you will probably succumb to the poison of it.

... Sooner or later you will see some man to whom the idea of wealth as mere wealth does not appeal, to whom the methods of amassing that wealth do not interest, and who will not accept monet if you offer it to him at a certain price.

At first you will be inclined to laugh at this man... I suggest that you watch him closely, for he will demonstrate to you that money dominates everybody except the man who does not want money. You may meet that man on your farm, in your village, or in your legislature. But be sure that, whenever and wherever you meet him, his little finger will be thicker than your loins. You will go in fear of him; he will not go in fear of you. You will do what he wants; he will not do what you want. You will find that you have no weapon in your armoury with which you can attack him; no argument with which you can appeal to him. Whatever you gain, he will gain more.

I would like you to study that man. I would like you better to be that man, because ... it doesn't pay to be obsessed by the desire of wealth for wealth's sake.'' __Rudyard Kipling, speech at McGill University, October 1907.

``... for after all, happiness (as the mathematicians might say) lies on a curve, and we approach it only by asymptote ...'' __Christopher Morley in The Haunted Bookshop. (Christopher Morley's father, Frank Morley, was a mathematician.)

``The insignificance of Roman achievements in the fields of mathematics, science, philosophy, and many of the arts is the best answer to those `practical' people who condemn abstract thought that is not motivated by utilitarianism. Certainly one lesson to draw from the history of the Romans is that people who scorn the highly theoretical work of mathamaticians and scientists and decry its uselessness are ignorant of the manner in which practical and important developments have arisen.'' __Morris Kline in Mathematics in Western Culture

"The death of Archimedes by the hands of a Roman soldier is symbolical of a world change of the first magnitude: the theoretical Greeks, with their love of abstract science, were superseded in the leadership of the Europeaan world by practical Romans... The Romans were a great race, but they were cursed with the sterility which waits upon practicality. They did not improve upon the knowledge of their forefathers, and all their advances were confined to the minor technical details of engineering. They were not dreamers enough to arrive at new points of view, which could give a more fundamental control over the forces of nature. No Roman lost his life because he was absorbed in the contempltion of a mathematical diagram." __Alfred North Whitehead in An Introduction to Mathematics

``Rome won the war, finally destroyed Carthage, and marched on to almost unimaginable heights of splendor, but not in science or mathematics. As bluntly practical as the soldier who dispatched Archimedes, the Romans were the first wholehearted exponents of virile living and bucolic thinking, and the first important people to realize that a modicum of brains can be purchased by those who have only money or power. When they needed any science or mathematics not already reduced to easy rule of thumb, the Romans enslaved a Greek. But they blundered when thay killed Archimedes. He was only seventy-five and still in full possession of his powers. In the five years or more of which the soldier robbed him, his truly practical mind might have taught the Romans something to ward off the fatty degeneration of the intellect which finally rendered tham innocuous.'' __E. T. Bell in The Development of Mathematics, p. 74.

``Really good mathematical ideas are hard to come by. They result from the combined work of many people over long periods of time. Their discovery involves wrong turnings and intellectual dead ends. They cannot be proved at will: truly novel mathematics is not amenable to an industrial `Research and Development' approach. But they pay for all that effort by their durability and versatility.'' __Ian Stewart in The Problems of Mathematics

``Considering how many fools can calculate, it is surprising that it should be thought either a difficult or a tedious task for any other fool to learn how to master the same tricks. Some calculus-tricks are quite easy. Some are enormously difficult. The fools who write the textbooks of advanced mathematics - and they are mostly clever fools - seldom take the trouble to show you how easy the easy calculations are. On the contrary, they seem to desire to impress you with their tremendous cleverness by going about it in the most difficult way. Being myself a remarkably stupid fellow., I have had to unteach myself the difficulties, and now beg to present to my fellow fools the parts that are not hard. Master these thoroughly, and the rest will follow. What one fool can do, another can.' __The Prologue to Calculus Made Easy: Being a Very-Simplest Introduction to Those Beautiful Methods of Reckoning Which are Generally Called by the Terrifying Names of the Differential Calculus and the Integral Calculus, by Silvanus P. Thompson, F.R.S.

"The 3-legged stool of understanding is held up by history, languages, and mathematics. Equipped with these three you can learn anything you want to learn. But if you lack any one of them you are just another ignorant peasant with dung on your boots."

"Age is not an accomplishment and youth is no sin."

"Any student can learn the truly tough subjects on almost any campus if he/she wishes - the professors and books and labs are there. But the student must want to.... I ask you never to forget this while we see how one can slide through, never do any real work, and still receive a bachelor of arts degree.... Some guidelines apply...: Don't pick a medical school or an engineering school. Don't pick a natural science that requires difficult mathematics.... You must pick a major... but it must not involve mathematics, history, or actually being able to read a second language. This rules out all natural sciences. ... It will be necessary to cater to the whims of professors who know no more than you do about anything that matters... but catering to your mentors is necessary in any subject not ruled by mathematics." __Robert A. Heinlein in "The Happy Days Ahead"

"For geometers and all those who proceed scientifically impose names on things only for concission of discourse and not to impoverish or alter the idea of the subjects of discourse. And they expect the mind always to supplement with the whole definition the short terms, which they use only to avoid the confusion caused by a multitude of words.

"Nothing acts more quickly and more effectively against the surprise attacks of captious sophists than this method, which we must always have ready for use, and which alone suffices to banish every kind of difficulty and equivocation.

"Those who willl not be satisfied with these reasons and continue in the belief that space is not infinitely divisible can never aspire to geometrical demonstrations, and although they may be enlightened in other things, they will have very little light in these, for it is easy to be a very clever man though a bad geometer."

__Blaise Pascal in "On Geometrical Demonstration"

"It is much easier to teach a mathematician to program than to teach a programmer some mathematics."

__Linda Banecker, Lockheed-Martin Management and Data Systems hiring manager, quoted in the October 1997 issue of SIAM News.

Some coaches, in their efforts to help the men estimate the necessary height of the arch before the descent of the ball on its way to the backboard, fix an imaginary spot approximately twenty-five feet in the air and twenty feet out in front of the basket. The player, when shooting, can imagine a line described by the course of a ball from this spot in the air to the basket. The ball which describes this imaginary line deflects into the basket on a carom shot.

This line should be the locus of the highest points of all arches used for rebound shots from any ordinary scoring distance directly in front of the basket. The ball in its arch after it leaves the player's hands describes a curve similar to a parabola, the highest point of which intersects the imaginary locus. The distance of the shooter from the basket determines the point of intersection of the crest of the parabola with the line. The closer-in the shots are made, the farther down on the imaginary line will be the point of intersection.

It is good pedagogy to teach the men to shoot for a direct looping hit into the basket. And this scheme of describing the imaginary line from a spot in the air is a means of stressing upon the players' minds the importance of shooting high. Most players shoot too low and too short. Should they overshoot, by correctly arching the shots, they will always have an extra chance for a goal on the rebound.

_from Chapter III, Individual Offense, of the 1924 edition of My Basket-ball Bible by Forrest C. Allen

The rules of our gamemust be thoroughly understood. We work some of the problems and read all of them. Working a problem is like cutting down a tree and reading a problem is like looking at a tree. We spend part of our time swinging axes to develop our muscles, and we spend part of our time looking around to keep us from being dolts. The mathematical and scientific forests really are interesting, and we should all enjoy chopping and looking at the scenery. We should all carry copies of (1.381) [a certain integral for the Bessel function of the first kind of order 0] so we can entertain ourselves the next time we get stranded in an airport or a jail. A student who wants to learn where differential equations come from and how they are used should pay careful attention to the problems. To solve a great many problems rapidly and thoughtlessly is a waste of time.

If in connection with some of these problems a student begins to feel that solving problems in applied mathematics involves so msny approximations that the whole business is utter nonsense, he is to be congratulated. He is perhaps approaching a point where he may begin to learn something about the manner in which mathematics is used in the sciences. __ Ralph Palmer Agnew, in his textbook Differential Equations.

``The box score, being modestly arcane, is a matter of intense indifference, if not irritation, to the non-fan. To the baseball-bitten, it is not only informative, pictorial, and gossipy but lovely in aesthetic structure. It represents happenstance and physical flight exactly translated into figures and history. Its totals - batters' credit vs. pitchers' debit - balance as exactly as those in an accountant's ledger. And a box score is more than a capsule archive. It is a precisely etched miniature of the sport itself, for baseball, in spite of its grassy spaciousness and apparent unpredictibility, is the most intensely and satisfyingly mathematical of all our outdoor sports. Every player in every game is subjected to a cold and ceaseless accounting; no ball is thrown and no base is gained without an instant responding judgement - ball or strike, hit or error, yea or nay - and an ensuing statistic. This encompassing neatness permits the baseball fan, aided by experience and memory, to extract from a box score the same joy, the same hallucinatory reality, that pickles the scalp of a musician when he glances at a page of his score of Don Giovanni and actually hears bassos and sopranos, woodwinds and violins.'' __ Roger Angell, in ``The Summer Game".

What are some of the reasons for resistance, resentment, rejection on the part of students?

First of all there is considerable impatience with the material. Surprisingly, this is often noticeable in the better students. But better students tend to demand instant understanding. Mathematics has always been easy for them. Understanding and intuition have come cheaply. Now as they move into the higher reaches of mathmatics, the material is getting difficult. They lack experience. They lack strategies. They don't know how to fiddle around. Understanding is accompanied by pains. It makes little impression to say that the material about to be presented is the end result of centuries of thought on the part of tens or hundreds of brilliant people. The desire for immediate comprehension is very strong and may ultimately be debilitating. (If I don't get it right away, then I never will, and I say to hell with it.)

The key idea is often brilliant but difficult. There may be a psychological unwillingness to accept that there is in the world a brilliance and an understanding which may exceed their own. There may be a sudden revelation that some higher mathematics is beyond them completely and this comes as a shock and a blow to the ego. The resistance may intensify and show up as lack of study, lack of interest, and an unwillingness to attempt a discovery process of one's own.

It is commonly thought that there are ``math types'' and ``nonmath types.'' No one knows why some people take to math easily, and others with enormous difficulty. For nonmath types resistance may be the honest reaction to innate limitations. Not everyone becomes a piano player or an ice skater. Why should it be different for mathematics? __ Philip J. Davis and Reuben Hersh in The Mathematical Experience.

"Much has been said by the students here in School about the lack of value and practical use of many things we teach in mathematics, physics and mechanics. Then too many of our graduates return and tell us they have never had need for this course or that in their practice. In most cases we find on investigation that they did not know enough about the subject to use it when opportunity arose so had to work around the matter in some other way and more often I suspect they knew so little of the subject that they failed to recognize the opportunity when it came up in the first place." __ Rolfe Rankin, in ``Mathematics in Engineering'', handwritten notes, Missouri Schol of Mines, c.1930-50

from Out West by Dayton Duncan

[Out West is the story of the author's journey retracing Lewis and Clark's route in a borrowed VW bus. He does more than just drive - he takes time to stop and actually do things along the way. Scattered throughout the book are Duncan's (sometimes painfully learned) Road Rules and other bits of wisdom. Most stand alone quite well, but to get the complete picture, or to understand the names of some of the corollaries, read the book.]

Road Rule 1: Never stop to ask directions, unless you are completely defeated; never stop to look at a map, unless you have to stop for something else. [Looking at a map is not prohibited, but don't stop to do it.]

Road Rule 2: Never buy highly perishable items from a store that's doing poorly or in an area built around the sale of history.

Road Rule 3: Never drive on the interstate unless there is no alternative.

Road Rule 4: Never eat at a nationally franchised restaurant; there's no sense of adventure, no diversity, no risk involved in patronizing them. They're uniformly bland.

Road Rule 5: Never retrace your route, unless you are completely defeated or at a dead end. Keep moving forward. And don't forget, you can't stop to ask directions or check your map.

Road Rule 6: Never call the bluff of an eighteen-wheeler, a Greyhound bus, a highway grader, a Buick or Cadillac with heavy chrome bumpers, a teenager driving any motorized vehicle, or a tractor pulling a wagon loaded with manure.

Where to eat: "Cafe" is better than "restaurant" and much better than "family restaurant". More important than "cafe" or "restaurant" is what goes in front of them to form the name. There are four categories, in order of preference:

1. First-name cafes. John Doe opens a Cafe in Anytown and names it "John's Cafe" (or just "John's). Given the name, you can usually assume John is still around and in charge. His name's up there in front of the public, so he's more likely to make sure they're satisfied. Joint-name or initial cafes are in this category: John and his wife, Louann, call their business "Lu-John's Cafe" or "L and J Cafe".

2. Last-name cafes. "Doe's Cafe" or, more likely, "Doe's Restaurant". A little more formal. The other problem is the possibility that John and Louann may have retired years ago, leaving John Jr., who never liked the restaurant trade to begin with, but is holding onto the business until he can sell it and move out of town.

3. Place-name cafes. "Anytown Cafe" or "Anytown Restaurant". It can be as good as the first category, and a certain sense of pride and place is carried in its name; or again, it may have gone through a series of owners and be hanging on more by tradition than menu.

4. Generic-name cafes. "Sunrise Cafe", "Oxyoke Restaurant", "The Chuckwagon", etc. Take your chances. At least it isn't a franchise.

[Dayton Duncan has a fifth group of small-town restaurants that he refuses to patronize. He calls them the Ks, places that use a "K" in their name when thay should use a "C"; Korner Kafe, etc. He avoids them on principle.]

Other things to watch for when looking for a place to eat:

Bad Signs

Good Signs

Road Rule 7: Devise your own system or theory on choosing where to eat. It's less important what the theory is (as long as it rules out national franchises) than it is that you have one and that you follow it.

Road Rule 8: If you're at all famous, don't let them bury you on the banks of the Missouri River. [Sergeant Charles Floyd, the only casualty of the Lewis and Clark expidetion, was buried on Floyd's Bluff, near present-day Sioux City, Iowa, in 1804. For various reasons, including the river undermining the bluff, resulting in the loss of portions of Floyd's skeleton, his remains were interred a total of six times, the last in 1900.]

Road Rule 9: If you want to meet people and learn about a town, the two best places to go are bars and churches. Bars are the only institutions in our society created for the specific purpose of conviviality; churches have a broader purpose, but doctrine requires the congregation to take in strangers.

Road Rule 10: The theology of the road forms its own religion, combining bits and pieces of other beliefs. It relies on technology (a vehicle), yet respects the forces of nature. Its deity is the Road Spirit; its principal practice is the pilgrimage.

Road Rule 11: The straighter the road you're on, the more your mind wanders a curving path. As your vehicle hurtles forward in space, your thoughts meander backward in time, often stopping to linger with a memory as if it were a historic marker on the roadside.

Road Rule 12: You can learn a lot from books, maps, and statistics, but the road is a better and sterner teacher.

Road Rule 13: A good explorer is able to adjust to new information and make the most out of the surroundings. One fork in the road or river may end in disappointment, but the other fork can get you back on track.

Road Rule 14: There are many strains of Road Fever, and an even greater number of folk remedies.

Road Rule 15: Trust your instincts. When they're wrong, you can blame it on bad luck. But when they're right, you can take the credit.

Road Rule 16: People are more willing to talk to travelers if you feign ignorance about their particular field of interest.

Trail Rule 1: Trust your horse.

Road Rule 17: Travelers and explorers in unfamiliar territory should expect conflicting advice from the natives about what direction to take, in fact about whether they should even proceed on.

Trail Rule 2: Never trust your horse.

Road Rule 18: One explorer's misery can be another's joy; one traveler's near defeat can be another's epiphany; one man's place to fear untimely death can be another's chosen spot to have his ashes spread.

Road Rule 19: Change is the only certainty. Whether it is measured in the life of a volcano, a nation, one person, or one split atom, the passage of time is change's passage.

Road Rule 20: Prejudices are like heavy furniture in a Conestoga wagon on the Oregon Trail. In order to keep moving forward, sometimes you have to toss them out, even if they are family heirlooms.

Road Rule 21: Always carry a first-aid kit in your vehicle. Indians and non-Indians often require "medicine" in their travels.

Road Rule 22: The trip home is a reverse image of the outward journey, like looking at the negative of a photograph you took not too long ago. Looking forward is looking back; each new sight is something seen before only from the opposite direction; counting mileage is a subtraction, not an addition, of the distance from home; memory is an image fading in the rear-view mirror.

Road Rule 23: You know you've explored a state correctly when you start anticipating the historic markers.

Road Rule 24: Always save some adventure for your return trip. It takes your mind off your destination.

Road Rule 25: Keep a journal of your travels. It is an invaluable tool to remind you of your trip, and the details within it are important for recounting history and the mark you leave on it.

Road Rule 26: The final value of any expedition is not what you failed to discover but what you found in its place; the important thing is not so much the dream you pursued but the fact that you pursued it. Looking back on your journey, what you remember most is not what you were searching for, but the search itself.

"Modern" philosophy begins with Descartes, or the positivist method of proceeding cautiously from the known to the unknown. Pascal, who appreciated the limitations of the finite mind in trying to know the infinite, said, "I cannot forgive Descartes." Nor can I. I am inclined to take a Buddhist view of Descartes. It was a fine gesture on the part of Descartes to say, "Cogito ergo sum." He was trying to prove the basic (and rather obvious) fact that he existed. In actual fact, however, Descartes' basis that he thought was pure, arbitrary assumption. But he had to start with something known, and he therefore blandly assumed that he thought. There is no reason why he could not, just as well, assume that he existed to prove that he thought. This is a kind of self-inflicted illusion of a logical mind. The most famous dictum of the father of modern philosophy had to start with a fallacy. Buddha would have asked Descartes briefly, "How do you know that you think?" If existence were an illusion, could not thinking be an illusion, too? Between the two, my existence and my thinking, I would more likely doubt my thinking. ... philosophy should be concerned with values, and values are strangely elusive to the application of the Cartesian method.

If we leave logical arguments alone, we find that intuitive insight is very much like common sense, which is not very common among "intellectuals." Common sense is based on experience, like woman's mysterious sixth sense. We call it the sixth sense because, like all complicated human experience, it can not be easily put into so many words. It appears mysterious because many of us do not have that extra-fine apparatus for synthesizing experience. It is by no means to be despised. When a wife says, "I feel," the husband ought to shut up. The sixth sense is subtler than logic, as calculus is subtler than geometry because it deals with more variables. We all feel or say someone looks like a Frenchman, or a Swede, or an Austrian, without our being quite able to give an exact definition of the French face or the Austrian face. ... It is all calculus, a science of variables, a seizing and sizing up of intangibles, based on past experience. We speak of luscious lips, or languid eyes, or deceitful looks without being able to set the geometric proportions. All we can say is that luscious lips are just luscious lips. Just as bats have developed an apparatus for detecting radar waves, so our mind has developed a capacity for registering experience by its own language faster than articulate words.

__ Lin Yutang, From the essay, "Intuitive and Logical Thinking" in the book The Pleasures of a Nonconformist.

The teacher in a classroom has almost total control of what takes place in that room. This fact has saved countless children from ill-conceived political and bureaucratic interference with schools.

__ Bob Witte, in "What I Have Learned From the Mathematics Community", The American Mathematical Monthly, 109 (2002) 585-594. This article is the text of an address delivered August 3, 2001 at MathFest 2001 in Madison, Wisconsin. Mr. Witte was employed for thirty-eight years by Exxon Corporation, and for most of his last ten years was Senior Program Officer for the Exxon Education Foundation.

Last modified August 19, 2002.