SHOULD I TRUST THAT LEVEE?

J.

David Rogers, Ph.D., P.E., R.G., C.E.G.

Karl F. Hasselmann Chair in Geological Engineering

Department of Geological Sciences & Engineering

Missouri University of Science & Technology

129 McNutt Hall, 1400 N. Bishop Ave.

Rolla, MO 65409-0230

We’ve

all been there; glued to our TV sets watching the roving reporter in their

raincoat, standing by some levee that’s flooded in the past, asking: Will it happen again?

Each time it begins to rain with intensity it

seems the media begins using roving reporters to broadcast “flood watch” segments. We all know the spots, usually near levees or

bridges, where flooding has occurred in the past. Along the

WHAT ARE LEVEES

?

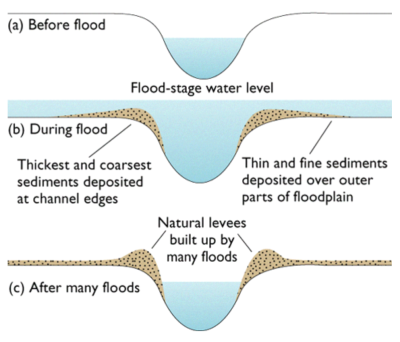

Rivers naturally prone to peak flood flows during

spring runoff develop natural overflow levees, deposited when the low flow

channel overtops its channel (see Figure 1).

Natural flow levees are typically comprised of more coarse grained

sediment, like sand, while the flood plain (Figure 2) is usually covered in

extremely fine silt. 75% of all the

sediment deposited upon the continent is overbank

silt, deposited upon well-defined flood plains.

Unfortunately, we have concentrated much of our societal

infrastructure upon these flood plains, and have thereby placed such property

in peril anytime the rivers begin to reach flood stage. In their natural state rivers tend to flow onto

their respective flood plains during peak runoff periods, generally during

the late spring months in

HOW ARE LEVEES DESIGNED

? In the 19th Century most towns were sited next

to the major rivers so that river-born commerce could access the community.

Levees, or dikes comprised of earth, were soon

built upon the river’s natural overflow levees as a means to provide protection

from flood flows (Figure 2). In the

Local reclamation districts and the Army Corps have since

joined forces to gradually heighten and extend great systems of levees along

those rivers normally prone to flooding, taking thousands of acres of flood

plain lowlands and “reclaiming” them for agriculture. Major sequences of Federal-aided levee construction

occurred in funding "sequences," in the 1930's and again, in the

late 1950's thru early 60's, providing the system of levees we see today. Following the disastrous 1927 and 1937 floods

along the lower CAN LEVEES BE DEPENDED

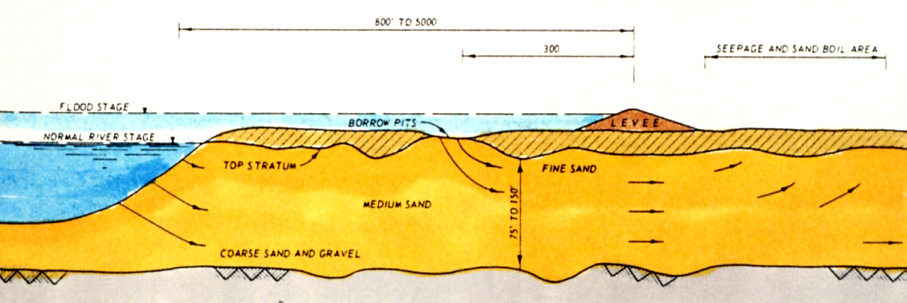

UPON FOR FLOOD CONTROL ? Being added onto every few decades, levees are

not engineered with the same precision, care, cost and engineering as other

hydraulic structures, such as dams. In

addition, levees extend for countless miles along major river channels, traversing

a heterogeneous assemblage of foundation conditions: crossing old channels,

sloughs, and oxbows perturbing any flood plain. The only constant of levees

is the inconsistency of their foundations. Because borrow pits and gravel quarries are

generally situated next to levees, a situation arises where seepage pressures

are introduced into the underlying flood plain

beneath the levee, and the duration of flooding dictates how long and

how far elevated seepage pressures will percolate beneath such embankments.

This situation is sketched in Figures 3, 4 and 5.

It only takes one break at a single discrete point to

flood the lowland protected by an entire system of levees. Given the variability of the levee foundations,

seepage-induced breaks are inevitable, especially in areas subject to localized

fluctuations of the water table, such as occurs when agricultural irrigation

practices change, or fields are left fallow (without summertime watering).

In the delta area the underlying soils are also consolidating each

year, causing differential settlement of the levees they support.

Longer duration floods tend to spawn greater hazard to

levees than short-term peak flows, as the longer the waterside of the levees

is inundated, the further flood-induced seepage can travel, beneath the levee,

and increases the possibility of destructive boils being formed on the landside

of the levee. It is for this reason that reclamation districts, responsible

for levee maintenance, employ crest patrols during flood stage, to continuously

inspect the landside toe of the levees for onerous levels of seepage. Such patrols have limited ability to make immediate

response, that usually consisting or placing sandbag walls around boils to

increase confining (hydrostatic) pressure at the exit (boil) point (Figure

4). Judicious placement of sandbags around boils

can dispel disaster, but not in every circumstance (Figure 5).

In a growing number of

cases studied by the Corps of Engineers, short-term, semi-explosive decay of levee integrity

has occurred, due to excessive straining of any foundation materials subject

to an upward-flowing seepage front, usually emanating from an old, buried

channel (lying beneath the levee). In

these cases, routine patrols with sandbags may be insufficient to dispel a

disaster. WHAT DOES THE FUTURE

HOLD ? Flooding is a natural peril that has been exacerbated

by wholesale development in In order to safeguard development on the flood plains,

we have attempted to control nature through catchment

of debris and safe conveyance of the flood waters to the ocean. This flood infrastructure requires extensive

maintenance in order to be effective. Any

number of factors could combine to create inadequate flood control at any

given time. Some of these factors include:

back-to-back storms, warm rainfall on snow pack; inadequate design storage

of reservoirs or channels due to lack of siltation

maintenance; volcanic erruptions clogging channels;

or the failure of any particular piece of the “chain of flow”. As our flood infrastructure ages, we can expect

more failures of the system to occur. For

instance, the loss of the radial gate on Folsom Dam in July 1995 was a failure

mode never seen before, tied to the age of the structure (built in 1955).

It is difficult to assess risk for causes of occurrence which have

yet to have ever occurred, but we can expect more. The passage of the National Flood Protection Act of 1968

created a federally-funded system of insurance for property owners living

in defined flood plains, and set rates according to relative risk of inundation.

As the levees held and insurance became universally available, these

agricultural tracts have slowly been giving over to urbanization, putting

more people at flood risk each year. Still, floods are the only natural peril currently

under a federally-mandated system of insurance, adjudicated by the Federal

Emergency Management Agency (FEMA). A

problem which continues to plague the NFIP is updating flood plains with increasing

development, adjusting rates with the changing risk of inundation, and determining

regional value indexes tied to inflation and cost of repair, which vary considerably

depending on the area. Levee or not, floods, like other natural perils, will

always be with us. J. David Rogers is the Karl F. Hasselmann

Figure 2 - Maximal loading

of a flood protection levee in Mississippi during the flood of 1973

Note school bus for scale and the seepage along the landside toe of the

embankment.

pressure of the soil cap. Boils can occur as conical spouts (shown at

right) or linear ridges (shown at left)

along the landside of the levee, and are usualy noticed prior to seepage-related

failures.

Figure 5

- Sand bags are commonly employed around recognized boils during

floods to increase

pressure

the excess pressure head and diminish hydraulic piping of fines from the

levee foundation.

Figure 6 - Levee failures can also be caused by massive

slope failures, such as that shown

here, on the river side of the Marchland Levee in Louisiana, which occured

in 1983.

E-mail Dr. J David Rogers at rogersda@mst.edu.

![]()