World War II was the largest and most violent armed conflict in the history of mankind. However, the half century that now separates us from that conflict has exacted its toll on our collective knowledge. While World War II continues to absorb the interest of military scholars and historians, as well as its veterans, a generation of Americans has grown to maturity largely unaware of the political, social, and military implications of a war that, more than any other, united us as a people with a common purpose.

Highly relevant today, World War II has much to teach us, not only about the profession of arms, but also about military preparedness, global strategy, and combined operations in the coalition war against fascism. During the next several years, the U.S. Army will participate in the nation's 50th anniversary commemoration of World War II. The commemoration will include the publication of various materials to help educate Americans about that war. The works produced will provide great opportunities to learn about and renew pride in an Army that fought so magnificently in what has been called "the mighty endeavor."

World War II was waged on land, on sea, and in the air over several diverse theaters of operation for approximately six years. The following essay is one of a series of campaign studies highlighting those struggles that, with their accompanying suggestions for further reading, are designed to introduce you to one of the Army's significant military feats from that war.

This brochure was prepared in the U.S. Army Center of Military History by Charles E. Kirkpatrick. I hope this absorbing account of that period will enhance your appreciation of American achievements during World War II.

M. P. W. Stone

Secretary of the Army

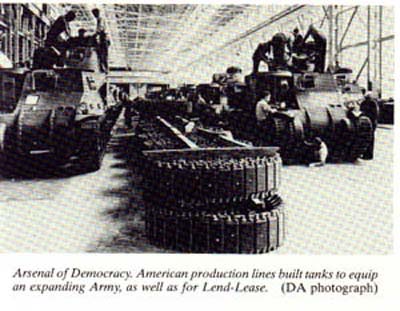

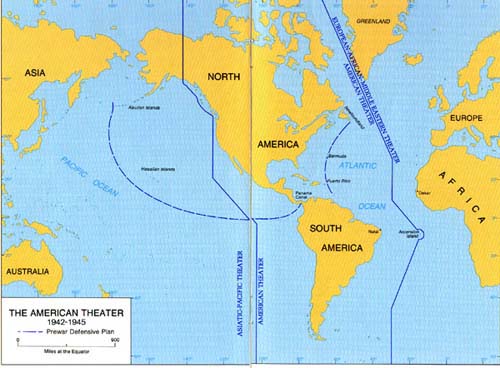

The defense of the Americas was the longest, most uneventful, and least heralded military campaign the United States conducted in World War II. Yet it was fundamental to Allied victory against the Axis coalition, for it guaranteed the security of the base that President Franklin D. Roosevelt earlier termed the "arsenal of democracy." It likewise guarded the Americas from attack while the United States raised and trained its armed forces.

Of all the Allied nations, the United States possessed the greatest economic and industrial power, and thus held the keys to victory. By 1945 American industry had manufactured enormous masses of military materiel, equipment that gave Allied soldiers on every battlefront a decisive advantage over their enemies. U.S. production lines, for example, turned out 88,410 tanks and self-propelled guns, as compared to only 46,857 built in Germany. Aircraft plants assembled 283,230 planes of all types, while Germany could manage only 107,245. The situation in the Pacific naval war was even more striking. After the Pearl Harbor attack, the aircraft carrier emerged as the principal capital ship. Between 1942 and 1945, Japan commissioned 13 of them, while American shipbuilders launched 137. American industry, safe in its continental bastion, unquestionably made an overwhelming contribution to the eventual victory.

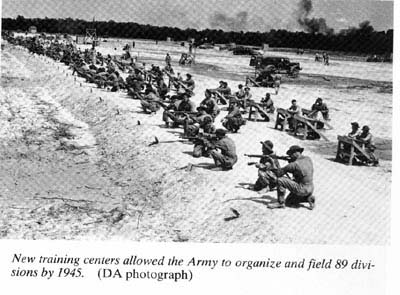

While industry expanded to meet the needs of supplying lend-lease and placing the military on a war footing, the Army commenced its own prodigious expansion from a force of less than 200,000 men to one of more than 8 million. Between the Pearl Harbor attack and the Allied invasion of North Africa a year later, the small existing professional cadre absorbed, equipped, trained, and organized an Army that finally amounted to 89 divisions and a large air force. Meanwhile, the services forged the logistical bases and ocean-spanning supply lines to sustain those divisions and air forces wherever they had to fight, and shipyards laid the keels for the thousands of merchant ships the vast logistical organization required.

During that critical year of preparation and indeed throughout the entire war, the physical security of the continental United States was virtually absolute. Not once during the war years did Axis forces interrupt American industry as it supplied its own armed forces and those of its principal Allies. Nor did Americans ever, after the few weeks of panic that followed the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, live in fear of invasion. Not once did foreign attack interfere with the training and organization of troops for foreign service. By achieving security within the Western Hemisphere, the United States was able to concentrate on the offensive very soon after the Japanese attacks in Hawaii and the Philippines. Thus the importance of the American theater totally transcended its prosaic conduct.

The prospects for American defense were extremely good because of the fortunate geographic position of the United States and its hemispheric neighbors. Separated from potential European and Asian aggressors by thousands of miles of ocean, the nation could expect ample warning of any attack. It was also clear that, despite recent impressive

advances in military technology, it would be extremely difficult for any foreign nation to make anything other than a nuisance raid on the United States. Bombing aircraft did not have the necessary range to attack across either ocean, and Japan lacked the bases in the eastern Pacific to support an attack by her navy on the American west coast. Analysts concluded that neither Germany nor Italy had a navy powerful enough or sufficiently long ranged, or a large enough merchant marine, to attempt an amphibious attack across the Atlantic.

U.S. policy in the late 1930s reflected those realities, although America's worldwide commitments during World War II have tended to obscure the traditional and basic concern of the government and its armed forces for the safety of the continental United States. War plans framed during the decades between the two world wars dwelt almost exclusively on repelling foreign invasion. The immediate defense of the United States lay in the hands of the Navy, which was positioned to control the seaward approaches to the American shores. The much smaller Army focused its attention on coastal defenses that could deny any potential enemy the use of a major port and on maintaining a small but well-trained mobile reserve that, supplemented by the National Guard, could reinforce any threatened portion of the coast.

The Munich crisis of September 1938 marked a turning point in American defense policy. By that time both military and naval staffs in the United States had noted rapid improvements in military technology and the greatly increased range and striking power of armed forces. Clearly, national defense was no longer a matter of securing the limits of American waters that had traditionally been defined by the range of cannon shot. After analyzing the situation, however, American staffs concluded that no foreign nation had gained the capacity to launch an attack on the United States directly across oceans, but only from land bases within the hemisphere. The basic defense policy was therefore modified, from the Army's point of view, to one of preventing the establishment of any hostile air base in the Western Hemisphere from which the United States might be bombed or from which an invasion could be supported.

By the time of the German attack on Poland that precipitated World War II, the new hemispheric defense policy was firm, at least in its broad outlines. The Navy, basing most of its strength in Hawaii, controlled all potential bases within reasonable striking distance of the Pacific coast of the United States and thus countered any possible Japanese menace. For the Army, defense of the Atlantic seaboard resolved itself into protection of the nation proper, with defense of the

Panama Canal Zone as secondary only to that of the continental United States because of the importance of the canal to the Navy.

The outbreak of war in Europe actually made the Americas more secure, as the Army's War Plans Division pointed out in a memorandum that stressed the degree to which Germany's armed forces were involved in Poland and, later, in Norway and Denmark. The powerful British Royal Navy, supplemented by the French fleet, controlled the Atlantic. As long as those navies existed, the German and Italian fleets could offer no threat to the United States, for no Axis invasion fleet could hope to cross the Atlantic in safety. The overwhelming power of the British and French Navies encouraged the United States in its decision to place the majority of its own fleet in the Pacific to provide security against any possible Japanese attack. Thus, although the United States remained officially neutral, the reality was that defense of America's eastern frontier tacitly depended in large part on the naval strength of the nations then at war with Germany. General George C. Marshall, Chief of Staff of the U.S. Army, affirmed as much in an October 1940 conversation with General Nicolas Delgado, Paraguayan Army Chief of Staff, when he confided that "as long as the British fleet remains undefeated . . . the Western Hemisphere is in little danger of direct attack." If the British fleet were defeated or surrendered, on the other hand, he cautioned, "the situation would become radically changed." Particularly in the months after the fall of France, maintenance of the British fleet became a touchstone of American policy.

Many of the key decisions that had to do with preserving the security of the United States in what came to be the American theater were made between 1939 and 1941. During these years the President and his military commanders began taking steps to prepare for the war many felt would inevitably involve the Americas. Chief among these were political arrangements with other hemisphere nations in which they agreed to cooperate with each other in the event of war.

While the oceans provided considerable security, by 1938 it seemed prudent to the President to keep any potential enemy many hundred miles away from the continent. After the Munich crisis— by which time the War and Navy Departments had already determined that Germany in combination with Japan posed the principal threat to the United States—President Roosevelt declared that the country had to be prepared to resist any attack on the entire West-

ern Hemisphere, from North Pole to South Pole. He made a further commitment to the Canadian government that "the people of the United States will not stand idly by if domination of Canadian soil is threatened by any other Empire," a reasonable promise in view of the thousands of miles of unfortified border between the two nations. The government forged similar ties with the nations of South and Central America, where German propaganda was intense and where there was considerable German economic involvement.

Once Canadian troops sailed to join other Commonwealth forces in Europe, the United States essentially assumed responsibility for ground defense of that nation. It was to the south, however, that President Roosevelt looked with greatest concern. In practical terms, as the Joint Planning Committee of the Joint Army-Navy Board pointed out in April 1939, the only way that any European nation could establish a viable base in the Americas would be to jump from Dakar, on the west African coast, to the bulge of Brazil, especially the area around Natal. The progress of the war underscored that possibility. Early German successes in Africa, coupled with Vichy French neutrality, exacerbated fears that Germany might easily reach Dakar and thus threaten the Americas.

The relative success of the Good Neighbor Policy helped to secure Latin American cooperation in the defense of the hemisphere. At the Buenos Aires Conference of 1936 the American nations had agreed both to consult whenever external events disturbed the peace of the hemisphere and to foreswear any intervention in each other's affairs. The various nations reaffirmed that compact in 1938, and in the Declaration of Lima they agreed to convene a conference of American foreign ministers to consult on plans and policies in the event of a non-American attack on any one of them. Such meetings took place in Panama in 1939 and in Havana July 1940.

Echoing President Roosevelt's announcement that the defense of the hemisphere did not rest solely on the shoulders of the United States, the 1939 Panama Conference of Latin American Nations responded to the outbreak of war in Europe by promulgating the Declaration of Panama, which established a neutrality zone of 300 miles into the Atlantic and the Pacific from which all belligerent warships were to be excluded. The fall of France in May 1940 prompted another meeting of the American states, this time in Havana, to consider what actions they should take about the New World colonial possessions of the Netherlands and France. Conferees finally agreed on an inter-American administration of such possessions if they were threatened by German or Italian occupation.

Meanwhile, the United States negotiated with Brazil for rights to establish an air base at Natal, a concession that was eventually granted, and with other states for base rights in the Caribbean.

The second element of President Roosevelt's diplomatic preparations for defense of the hemisphere involved the United Kingdom. German successes during the spring of 1940, and particularly the escape of the battle cruiser Bismarck into the western North Atlantic, revived fears that Great Britain might not survive and spurred the President's interest in obtaining bases to defend against any possible German attack by way of Newfoundland and the St. Lawrence estuary. Such apprehensions, as well as the spreading naval war in the Atlantic, inevitably encouraged the President and his advisers to expand the defensive perimeter that they considered necessary for the security of the country. The Destroyer-Base Agreement of 2 September 1940, seen in this light, was as much a matter of American self-interest as it was of altruistic aid to the British. Under its terms, the United States secured 99-year leases to bases on Newfoundland, Bermuda, the Bahamas, Jamaica, St. Lucia, Antigua, Trinidad, and British Guiana.

After September 1940, American policies of hemisphere defense continued to merge with a broader policy of supporting the nations resisting Axis aggression. By early the next year that conviction had brought further Anglo-American cooperation, specifically in the ABC-1 staff talks that settled the policy the two nations would follow if the United States entered the war, and to the Lend-Lease Act of 11 March. In this twilight time between peace and war the nation moved steadily away from neutrality and toward belligerency, as the armed forces began the transition from a peacetime structure of command to a wartime theater organization.

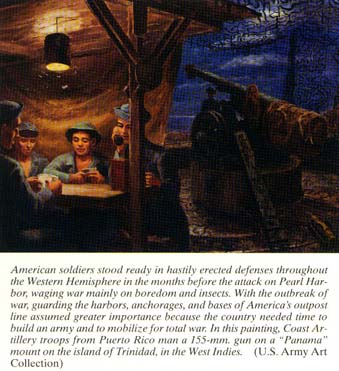

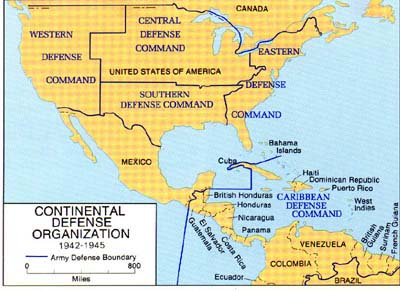

In February 1941 the services organized the Caribbean Defense Command, and throughout the year the United States continued the buildup of other Atlantic bases. At the end of May the War Department made plans to send a garrison to Greenland, and in June President Roosevelt agreed to dispatch American troops to relieve the British garrison in Iceland. Within the United States the Army created four strategic areas known as defense commands, refined plans to protect the country against possible ground and air attack, and began reinforcement of the outlying Pacific garrisons.

The five editions of the RAINBOW war plans reflected the changing circumstances in which the United States found itself. RAINBOW 1, operative from the start of the war in Europe, focused on enforcement of the Monroe Doctrine. By mid-1940, with the growing

fear that Britain might succumb to German attack, emphasis had shifted to RAINBOW 4, which planned for defense of the United States without the aid of the United Kingdom and other European Allies. After the Battle of Britain, with the presumption that the Royal Navy would continue to secure the Atlantic frontier, Navy and War Department staffs began to think in terms of RAINBOW 5, which hypothesized sending American forces to fight in Europe and Africa. Regardless of the overall intent, however, the prerequisite in each edition of the RAINBOW plans was defense of the hemisphere. The sensitive question was exactly how American forces were to accomplish that when war was not yet declared.

By the end of 1941, American defenses were arrayed basically in two great arcs. In the Pacific the defensive line stretched from the Aleutians, through the Hawaiian Islands, to Panama, with advance bases in the Philippines and strategic Pacific islands. In the Atlantic the defensive boundary now reached far into the ocean, from Newfoundland to Bermuda and then to Puerto Rico and the Windward Islands, which guarded the approaches to Panama. In May 1941 President Roosevelt issued orders to all base commanders to resist any attack by forces "of belligerent powers other than those powers which have sovereignty over Western Hemisphere territory." Recognizing that those instructions were vague, the President amended them on 11 September, when he announced a fifty-mile interdicted zone and a "shoot-on-sight policy." Thus by late October American forces were committed to destroying any German or Italian ships or aircraft that appeared anywhere in the western Atlantic zone.

The Navy was reasonably prepared for such action, since it had the mission of defending America's coasts. The Army and its air forces, on the other hand, had only begun their expansion. Some relief came in June 1941 when the Germans attacked Russia. Now deeply committed on the European and Russian fronts, Germany could spare few naval, air, or ground forces for action in the Atlantic theater. In the Pacific, however, Germany's Operation BARBAROSSA against Russia opened opportunities for the Japanese Empire. With the Soviet Union preoccupied in repelling the German invasion, the need to reserve substantial forces to counter Russian Pacific strength no longer inhibited Japan. The probability of war in the Pacific therefore increased after June. When war came, the United States was still in the midst of economic and manpower mobilization and unready to fight. Given these constraints, hemispheric defense remained the essential first mission of the Army and Navy.

The Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, expanded a spreading European war into a world war. A joint session of Congress declared war on the Japanese Empire on 8 December 1941. It was not until the 11th that Germany and Italy declared war on the United States. When Congress repined with a declaration of war on each of those states, it simultaneously enacted legislation to allow American forces to be employed in any part of the globe and extended the draftee term of service to six months after the end of hostilities. The War Department hastily mobilized existing ground and air force units to repel invasion along the west coast of the United States and to reinforce the garrison in Hawaii. At the same time, the essence of military planning, already well under way in late 1940 and early 1941, was to carry the war to America's enemies as soon as possible. Offensive action overseas would obviate the need for elaborate defenses at home. Dispassionate military analysis soon demonstrated that there was no more real threat of actual invasion of the United States after the Pearl Harbor disaster than there had been before it, but it took some months for public fears to dissipate.

At the beginning of 1942 the presumed risk of direct attack spurred the creation of Eastern and Western Theaters of Operations, which included, respectively, the east and west coasts of the United States. These had been the old Eastern and Western Defense Commands. The two theaters contained the majority of the trained combat troops and squadrons in the United States. The lack of any tangible danger, however, permitted General Headquarters to reduce these establishments in short order. It abolished the Eastern theater in March 1942 and the Western theater later in the same year. Manpower remained the limiting factor. It was impossible for the Army both to garrison the long frontiers of the United States and to superintend the training of the mass Army needed to fight an offensive war. Offensive action had the clear priority, and almost immediately the manning of defensive garrisons began to take second place to the training needs of the Army.

This was most immediately apparent on the east coast, in the Atlantic bases, and in the Caribbean. Comparatively secure against German surface attack, the bases scattered across America's eastern perimeter needed few Army troops to defend them, and the small detachments were progressively reduced in size in 1942 and 1943. The only fighting in these regions was an Allied naval antisubmarine

war. The Army's role was limited to patrols by Army Air Forces units stationed on the east and Gulf coasts and in the Caribbean.

Distance, the complications of the European war, and a curious ineptitude combined to limit the effectiveness with which the German intelligence service conducted its activities in the Americas. Once Germany declared war on the United States, the remaining diplomatic and commercial links between the two countries were sundered. Admiral Wilhelm Canaris' Abwehr organization seemed at a loss as to how best to get its agents into the United States and Canada. As it turned out, the only practicable method involved the use of submarines to land agents on deserted or sparsely populated American beaches. U-boats, however, had other and far more important missions, from the perspective of the overall German war effort. Consequently, relatively few German spies arrived in the United States.

Those who did reach the hemisphere displayed a remarkable naivete about American customs, and they were poorly briefed about their targets, in the case of saboteurs, and about their intelligence objectives, in the case of agents. The most spectacular case was the landing of eight agents along the Florida and Long Island coasts in early 1942. American law enforcement officers, including FBI agents, detected the Germans almost as soon as they got ashore

and rounded them up in short order. A military tribunal under the presidency of Lt. Gen. Frank J. McCoy sentenced six to death; the remaining two received life sentences.

One of the last German missions landed from a U-boat in Maine in late November 1944. By that point in the war the Germans had evidently given up on penetrating American military organizations and planning staffs. The 1944 mission, consisting of a German and a renegade American, merely sought to purchase, digest, and forward to Germany current technical information that appeared in open publication in the American press. These agents, too, were swiftly caught and imprisoned. In contrast to the effectiveness of the Abwehr's European operations, the few spies Germany sent to the Americas did little to justify their expense.

The War Department's limited role in the anti-espionage campaign was clearly more a matter of form than function. The Coast Guard needed little help to patrol the beaches in the first place, and infantry training was poor preparation for such routine security duties. As it became obvious that the normal law enforcement machinery of the country was adequate to cope with the problem, the Army withdrew its soldiers to other and more important duties.

The Army's remaining task in the theater was the modernization of key coast artillery establishments and the construction of new airfields as prudent preventive measures. Coast artillery fortifications

declined in number but grew vastly in defensive capability. Coastal airfields were quickly supplemented by many others as the Army Air Forces began a vast training program. The high volume of training flights, many of them in coastal areas along the Gulf coast, supplemented standing patrols, as did the activities of the Civil Air Patrol, as directed by Army Air Forces officials.

The Army speeded up completion of immediate prewar programs for large-caliber batteries to supersede as many as two dozen models of six different-caliber guns at many smaller coast artillery installations at key harbors and waterways. Among the best examples of this upgrade were the harbor defenses of Narragansett Bay, where new, two-gun 16-inch batteries at Point Judith and Point Sakonnet replaced six older forts and more than three dozen obsolete guns. In the Puget Sound two such guns guarded the entire waterway, supplanting more than forty prewar weapons in three major forts. At Cape May and Cape Henlopen new batteries that could range out as much as sixteen miles completely closed the mouth of the Delaware Bay to enemy ships, rendering an older string of forts along the Delaware River to Philadelphia unnecessary. At the same time, the older, smaller-caliber guns that had been replaced remained valuable, and the Army transferred them to Allied nations to build up their own coast defenses.

Coast defenses benefited from technical improvements as well. Although optical range-finding remained an important gunnery technique, the Army installed radars at the new batteries to enhance fire control. Major construction along the central and northern Atlantic seaboard, at Newfoundland, at Puerto Rico, and at various points on the west coast and Hawaii combined modern, long-range guns and the most up-to-date radar systems into a formidable obstacle to invasion.

Construction proceeded feverishly during the year after Pearl Harbor, but it gradually slowed as military and naval campaigns in the various theaters reduced the enemy threat and, as a consequence, the urgency. Although the Army carried through about two-thirds of the planned 150 new batteries, it also quickly recognized that military technology had made coastal forts largely obsolete. Economies swiftly followed, as the War Department stripped regulars from the batteries and turned them into the cadre for the antiaircraft artillery units being organized to accompany the field army into battle. In practice the Army transferred the majority of its combat units, as well as its operational air force squadrons, on the east coast to other duties. By mid-1944 the construction program had come to a virtual halt, with many of its remaining units canceled and the construction of others suspended in mid-course. During the war, however, the coast artillery program consumed around $250 million, and by 1945 it had produced the most extensive and comprehensive coastal fortifications system in the history of the nation.

In the Central Defense Command, where only the Sault Ste. Marie Canal and St. Mary's River waterway needed protection, the Army followed the same pattern of reducing its initial commitment of combat troops. The two waterways connect Lake Superior with Lake Huron and are the conduit through which iron ore is shipped to the foundries. Again, the chance of direct attack was remote, but it was not beyond believing that the Germans might sacrifice limited forces in a one-way attack to destroy the locks. U.S. and Canadian forces cooperated to guard against the major possibilities of attack, bombing and sabotage. In April 1942 the Army stationed a force of about 7,000 men there, while the Canadians erected antiaircraft defenses under American operational control and authorized the United States to build radar stations across northern Ontario for early air-raid warning. As the war progressed, the possibility of attack subsided, and the Army reduced its security forces to a single company of military police before the end of 1944.

It appeared in January 1942 that the defenses of the west coast had been breached by the attack on the U.S. Pacific Fleet and the Hawaiian Islands. Two weeks of panic followed the Pearl Harbor attack as anxious citizens made many erroneous "sightings" of the Japanese fleet. The Army rushed antiaircraft units to defend the California oil industry; critical aircraft plants at Los Angeles, San Diego, and Seattle; and naval shipyards in the Puget Sound, in Portland, San Francisco, Los Angeles, and San Diego. By the end of February almost 250,000 troops had arrived to defend vital installations on the west coast, a task for which Army ground combat units were neither intended nor trained. General Marshall's chief concern was that the public fear of imminent invasion would freeze this force in a perimeter defense of the coast at a time when these regulars were desperately needed to train the citizen army being mobilized by the Selective Service System. Within six months, however, the demand for such defenses abated as Japanese intentions became clearer. If there had ever been a risk of west coast invasion, it disappeared after the Battles of the Coral Sea (6-8 May 1942) and Midway (3-6 June 1942), which crippled the Japanese aircraft carrier force that would have been essential to an attack on the Amer-

ican mainland. After the results of Midway became clear, the Army began to stand down its defenses on the west coast, reassigning its Air Forces units and antiaircraft forces to other duties. Thereafter, the War Department adopted a "calculated risk" policy that gave priority to mobilization duties rather than to passive defense.

The peak of Army involvement in continental defense came in July 1943, when 379,000 men were so assigned. That number is deceptive, however, for only 185,000 of those men were combat troops, and among the combat troops, fully 140,000 were in antiaircraft and coast artillery units. Already, infantry, artillery, and armored force units were engaged in other duties. A similar situation prevailed in the Army Air Forces, where aircrew were increasingly assigned to training units. The elaborate continental air defense system began to deteriorate by mid1943 because the coastal areas were so saturated by training flights that the aircraft-warning system could no longer function. Similarly, from a peak strength in 1942, Army forces assigned to Atlantic bases declined sharply as the possibility of German surface attack declined.

Other nations in the hemisphere played a role in the defense of the Americas, chiefly by patrolling their coastal waters. At the Rio de Janeiro Conference of Foreign Ministers in January 1942, the delegates voted to create an organization to coordinate such activities, the Inter-American Defense Board, which convened in Washington, D.C. Lt. Gen. Stanley Embick, a former deputy chief of staff recalled from retirement, served as chairman during the critical year 1942-1943. Most of the Latin American countries on the board were represented by their military, naval, and air attaches. The board held sessions roughly twice a month to discuss all matters having to do with improving the defenses of the Western Hemisphere and adopted resolutions embodying recommendations on those issues. The United States also conducted bilateral negotiations with individual nations and arranged to send ammunition and equipment to bolster the defenses of various American states.

Special arrangements existed with Mexico. In the course of prewar negotiations, Mexico agreed to permit American aircraft to stage through Mexican airfields to reinforce the garrison in Panama. After Mexico entered the war in May 1942, the two nations developed even closer ties. In the weeks after Pearl Harbor, General Lazaro Cardenas and Lt. Gen. John L. DeWitt made joint plans for the defense of the Mexican northwest and the southwest of the United States. Their local arrangements to secure the Pacific coastal region became the basis for formal agreements concluded later in the war.

As the war proceeded, events proved the validity of the War Department's early estimates about German and Japanese ability to attack the hemisphere. Direct attacks on the United States were extremely rare, and they were concentrated almost exclusively in the Pacific. The Atlantic war was a naval one. German submarines enjoyed their greatest successes before the middle of 1942, when the convoy system, aerial patrols, and improved antisubmarine tactics gave the Allies the upper hand in the Atlantic, Caribbean, and Gulf of Mexico. Fairly soon after the United States became involved in the war, German U-boats were driven out of American waters. In any case, submarines were the concern of the Navy and, to a lesser extent, the Army Air Forces. The Army's ground participation in the Atlantic defense was chiefly in helping the Coast Guard patrol the beaches to forestall the landing of German agents in 1942 and 1943.

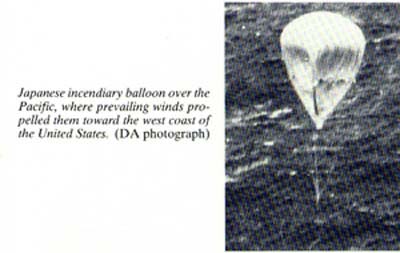

The west coast actually saw a limited amount of warfare. Submarines of the Japanese 6th Fleet performed reconnaissance and struck the sea lines of communication. Around the middle of December 1941, nine submarines arrived in American waters for the start of what was to be eight months of operations. Four of these boats eventually made attacks on coastal shipping, sinking two tankers and damaging one freighter. On 23 February 1942 the submarine I-17 surfaced near Santa Barbara and used its deck gun to fire thirteen 5.5-inch shells into oil installations, although with negligible damage. On the night of 21-22 June 1942, a submarine rose to the surface at the mouth of the Columbia River in Oregon and fired about a dozen 5.5-inch shells at Fort Stevens, a coast artillery fort. Militarily insignificant, that attack marked the first time since the War of 1812 that a foreign enemy had fired on a military installation in the continental United States. In early September 1942 the final Japanese submarine attack on the American coast during the war took place in reprisal for the Doolittle raid on Tokyo the previous April. The I-25, which carried a float plane, launched its aircraft off the Oregon coast on the 9th of the month. The airplane dropped an incendiary bomb on a forested mountain hill near Brookings, starting a small forest fire that local authorities quickly extinguished. The I-25 then sank two tankers before leaving for Japan.

Unlike the American Navy, the Japanese never reconsidered submarine doctrine during the war. They continued to concentrate their submarines on attacking warships rather than merchantmen. The failure of Japanese submarines in the Pearl Harbor attack also apparently led Japanese naval commanders to discount their value. There was consequently no Japanese submarine plan that paralleled

the German offensive in the Atlantic or the enormously successful American campaign against the Japanese merchant fleet across the Pacific. As a result, American commerce, especially in American waters, remained unmolested after the fall of 1942. Later Japanese attacks on the American mainland were limited to a series of incendiary attacks by free balloons, all of very limited consequence.

Just as the Battles of the Coral Sea and Midway deflected the Japanese from any possible attack on the west coast of the Americas, the progressive defeat of the German Afrika Korps in Libya removed the already remote possibility that the Germans would cross to Brazil from West Africa. The Allied landings in North Africa in November 1942 thus had the secondary effect of leading to enhanced Western Hemisphere security. The corollary was that Army units assigned to the American theater were drawn down at the same rate, concentrating instead on troop training and overseas deployment. The Army's continental defense structure remained until 1945, but after 1943 it was a mere shell of the original organization.

The history of the American theater encompassed no great battles, and the Army played no significant part in its few skirmishes. Thus it passed almost unnoticed. In a sense, however, this campaign was the most important of the entire war, for success in securing the nation proper from external attack was the foundation for Allied victory. Secure from outside attack, the nation built armed forces capable of global action and developed, manufactured, and distributed the modern weapons to equip both these forces and those of many of America's Allies.

Offense lies at the heart of success in warfare, and the officers in the War Plans Division of the War Department General Staff had already concluded in 1940 and 1941 that the best way to win a war was to land substantial forces on the continent of Europe and attack directly into Germany as early as possible. Well before Pearl Harbor, those planners had made a cross-Channel invasion from the United Kingdom to France the basis of overall strategy. It is not an exaggeration to say that invasion of the continent of Europe was the final goal toward which all American military operations aimed and that, for the United States, success in such a landing was the one step that would ensure victory.

Ancillary plans for defense of the United States were clearly affected by that basic strategic scheme. From the moment war started,

War and Navy Department staffs sought to liberate their units from passive defense so that they could build the forces and the logistical structure necessary to carry the war to the European continent. War in the Pacific was a complication that slowed down the process, but it did not deflect the United States from its basic intention. In early 1942 the nation's military leaders reached the conclusion that fundamental hemispheric security existed and turned their attentions entirely to offensive action. The possibility of minor, although possibly spectacular, enemy attacks on the United States still required vigilance and the dedication of a limited number of soldiers and ships, since such an attack could inflame public opinion and thus have a disastrous effect on mobilization for overseas warfare. Of the real security of the Americas, however, there was no doubt. Army bases in the hemisphere were more springboards for action abroad than actual defenses by 1943.

Militarily, the early achievements of the campaign were a response to fears greater than what the facts merited. Lurid articles in the press about the danger of a Nazi invasion of Latin America, widespread in the years immediately before the war, never had much basis in reality. Responsible military analysts had determined well before Pearl Harbor that neither Germany nor Italy had the logistical wherewithal to force a landing in the Americas in any strength. Regardless of. their apparent strength in Europe, both states remained continental powers, not world powers.

The most significant action in protecting the hemisphere was undertaken by the British when they established a base in Iceland, forestalling any similar German move. Creating an Icelandic base was within German abilities, and would have enabled the German Navy to base reconnaissance aircraft and submarines well out in the Atlantic. Given such a base, it would have been quite possible for Germany to close the Atlantic sea routes and thereby defeat Great Britain. Subsequently, such a base might have been used as a springboard for attacks into the Americas via the St. Lawrence River. Allied operations in Iceland, not a part of the American theater, thus nonetheless had a great influence on American security.

Cooperation among the American nations during the war was especially noteworthy. The prewar diplomatic agreements to consult about the best interests of the hemisphere led with little dissent to cooperative actions aimed at securing both the countries involved and their territorial waters. The joint defensive plans framed by the United States and Mexico were unique in the histories of both na

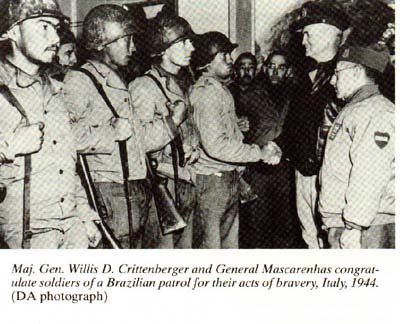

lions, in that they authorized the free movement of the armed forces of each country into the territory of the other if the military situation demanded it. Later in the war, Mexico sent its 201st Fighter Squadron to join United States air forces fighting on Luzon, and Brazil dispatched an expeditionary force of one infantry division and supporting troops to Italy, where it fought under the command of U.S. Fifth Army. General J. B. Mascarenhas de Moraes commanded more than 25,000 men in 229 days of continuous combat. The Brazilian Air Force also sent a fighter squadron to Italy, and the Brazilian Navy escorted convoys across the Atlantic and into the Mediterranean. This was the first time that a South American country had ever sent an expeditionary force overseas.

Notable as were those military achievements, the cooperation and consultation before and during the war were even more important, since they left a lasting legacy. In the Inter-American Defense Board, each of the countries in the Americas had the means to express its own concerns and seek the assistance of its neighbors in dealing with them. The board's consultations continued long after the Axis threat to the Americas was little more than a memory, and

they proved so worthwhile that the member nations decided to maintain the organization after the war.

In broad terms, the defense of the Americas in World War II stands at the end of an era in American security. Although the continental United States remained safe throughout World War II, chiefly because of geography, worrisome developments in weapons technology steadily eroded the value of the nation's distance from its enemies. Before the war, aerial bombardment of the hemisphere was impossible; by 1946, there was no doubt that the Americas then lay, or would soon lie, within range of enemy attack. Since distance no longer conferred security and time for mobilization, the United States was now faced with the need to maintain a standing peacetime military organization.

Those wishing to consider the American defense campaign in greater detail should refer to the relevant volumes in the U.S. Army in World War II series, in particular to Stetson Conn and Byron Fairchild, The Framework of Hemisphere Defense (1960); Conn, Fairchild, and Rose C. Engelman, Guarding the United States and Its Outposts (1964); and Mark S. Watson, Chief of Staff: Prewar Plans and Preparations (1950). On the development of Western Hemispheric military cooperation, see J. Lloyd Mecham, The United States and Inter-American Security (1961), and John Child, Unequal Alliance: The Inter-American Military System, 1938-1978 (1980). For a survey of one of the major Latin contributions to World War II operations, see J. B. Mascarenhas de Moraes, The Brazilian Expeditionary Force By Its Commander (1966, 2d ed.).