The Concept of "Reasonable Care" on Unstable Hillsides

J. David Rogers 1

and Robert B. Olshansky 2

1 UM-Rolla Dept. of Geological Engineering

129 McNutt Hall, 1870 Miner Circle, Rolla, MO 65409

2 Dept. of Urban and Regional Planning,

University of Illinois,

Urbana 907 1/2 W. Nevada St., Urbana, IL 61801

Judicial decisions involving earth surface processes have trended over the past two decades toward rejecting many of the old common law rules of liability. The courts are moving away from specific doctrines of liability and toward more case specific application of the idea of "reasonable care."

The term "reasonable care" is closely related to the legal definition of negligence, generally defined as the failure to exercise the degree of care appropriate to a situation. Whether or not a person has been "reasonable" depends on the particular facts of the case. Black's Law Dictionary defines "reasonable care" as follows: "That degree of care which a person of ordinary prudence would exercise in the same or similar circumstances ... Due care under all the circumstances. Failure to exercise such care is ordinary negligence." Hence, both "negligence" and "reasonable care" are relative terms that must be judged for each situation. The judgment of whether or not an actor has behaved "reasonably" is up to a jury, according to the testimony presented to them.

This paper illustrates the recent trends in the law with three California cases: Keys v. Romley (California Supreme Court, 1966), Sprecher v. Adamson (California Supreme Court, 1981), and Easton v. Strassburger (California Appellate Court, 1984).

SURFACE WATER LAW: KEYS V. ROMLEY

The case of Keys v. Romley (64 Cal.2d 396, 1966) changed the law of surface water in California, and is therefore of obvious importance to landslide cases. In this decision, California followed Minnesota, New Hampshire, and New Jersey in adopting the "rule of reasonable use" of surface water. This rule has since been adopted by at least eight additional states (Tank, 1983).

To understand the rule of reasonable use, one must first examine the other two doctrines of surface water law in the U.S., the "common enemy doctrine" and the "civil law rule" (Kinyon and McClure, 1940). The common enemy doctrine says that a landowner has an unqualified right to fend off surface water from his property, irrespective of the downhill effect; each landowner is responsible only to himself in diverting the water off his property. The civil law rule is a modification of the common enemy doctrine. This rule states that the lower landowner must accept drainage from above, as under the common enemy doctrine, but the upper owner may not modify the natural flow so as to increase the downhill burden. This rule, a clear statement that the upper owner may not divert natural flow, to the detriment of those below, was the law in California prior to Keys.

The Keys v. Romley case concerned two properties in Walnut Creek, Contra Costa County. In 1956, Keys built an appliance store. Construction involved some excavation and piling of the spoils at the rear of the property. In 1957, Romley constructed an ice rink above and behind the appliance store. This construction involved grading, leveling, paving, and the placement of four roof downspouts that directed run-off onto Keys' property. In 1957, Keys built a parking area and added to the soil pile. In the autumn of 1958, Keys removed this pile. Between January 1959 and January 1962, Keys' appliance store was flooded repeatedly, despite attempts to divert surface water. Finally, in 1962, by mutual agreement after litigation had begun, Romley constructed a concrete curb on the property line, to prevent flow onto Keys' property.

The lower court enjoined Romley from interfering with the natural flow of water to Keys' detriment, based on the civil law rule. The court also awarded $4,384.78 in damages to Keys. The California Supreme Court reversed this decision, however, using this case as the opportunity to adopt the rule of reasonable use.

The rule of reasonable use applies to both uphill and downhill owners, requiring uphill owners to take reasonable care when diverting surface water and requiring downhill owners to take reasonable precautions to avoid injury and damage from surface water. The Keys court declared that surface water cases should not be decided by an unvarying rule, but rather by the facts of the particular case, as determined by a jury. The Keys case was therefore sent back to the trial court for a decision.

It is often the case in major judicial decisions that the factual situation does not appear to warrant a landmark decision. Historically, a court knows what changes it would like to make in the law, and it takes the first suitable case that comes its way. Such appears to be the situation in Keys. The facts, as reported in the Supreme Court decision, strongly suggest to most readers that the balance of reasonableness lies in favor of Keys (who would also have won the case under the civil law rule). This case does not appear to be particularly unique nor worthy as a foundation for a new legal theory, but it provided the Court of that era (1966) with a case upon which to build the doctrine of reasonableness. Indeed, according to Keys' attorney (Ganong, 1986), when it was returned to the trial court, the case was decided in Keys' favor after a brief hearing.

The rule of reasonable use is, to attorneys, subtly different than the older negligence concept of reasonable care. To the rest of us, however, the concepts appear quite similar. This reasonableness rule forever erased absolute tests or definite rules for liability exposure from surface water damages. Rather, each case is to be decided on its own merits, based on the behavior of the players involved, the apparent gravity of the harm, the respective duties owed to one another, and the knowledge each had or should have had.

NATURAL SLOPES: SPRECHER V. ADAMSON

It is an old common law rule that an owner of natural unimproved land is immune from liability for the effects of the condition of his land on offsite persons or property. If a damaging landslide is related to man-made conditions, then the uphill owner can be tried for negligence on the basis of the reasonableness of his behavior (or inaction) and the connection of his behavior to the onset of land slippage. But, if the landslide occurs on natural, unaltered land, then there was no basis for legal action. This reasoning is analogous to the civil law rule of surface waters, previously described above.

There has generally been an exception to this rule in regard to decaying trees that fall and cause injury on neighboring properties (Gibson v. Denton, 38 N.Y. Supp. 554, 1896; Noel, 1943). This is because courts of past eras believed it is relatively easy to recognize decaying trees and remove what is intrinsically a significant hazard to neighbors, particularly in urban areas. An increasing number of states have declared such an exception to the rule in these cases.

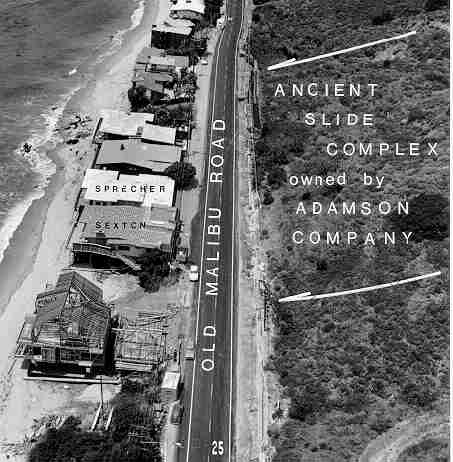

Sprecher v. Adamson (30 Cal.3d 358, 1981) was a case involving a landslide in the Malibu beach area of Los Angeles County; a pricy seaside area long known as a haven for Hollywood starlets. The Adamson Companies owned a 90 acre parcel of unimproved land uphill from Old Malibu Road. The parties in the case did not dispute the fact that Adamson's land was natural and was on part of a periodically active ancient landslide complex that had been recognized for many decades. Sprecher lived in a beachfront house across Malibu Road from the Adamson property, at the toe of the landslide (fig 1).

In March, 1978, following heavy rain, portions of the ancient slide complex above Sprecher reactivated, pushing Sprecher's house and causing it to rotate slightly and press against his neighbor's house. The neighbor, Sexton, filed suit against Sprecher, and Sprecher filed suit against Sexton, the Adamson Companies, and Los Angeles County (they were responsible for the roads, and also for approving caisson piers Sexton had installed to protect her property). The cases between Sprecher and Sexton were settled by their insurance carriers, and the trial court found in favor of the County. The California Supreme Court case was Sprecher's appeal of the decision declaring the Adamson Companies to be immune and not subject to trial because of the traditional common law immunity from damage claims for owners of unimproved properties. California Supreme Court decision in Sprecher v. Adamson discarded the common law immunity and declared that each case must be tried on its own merits, according to the principles of negligence. Hence, the Supreme Court required the trial court to decide whether the Adamson Companies exercised reasonable care, considering all the circumstances (likelihood of injury to plaintiff, probable seriousness of such injury, the cost of reducing or avoiding the risk, the location of the land, and the landowner's degree of control over the condition). This case was sent back to the trial court with that instruction.

As with Keys, the facts of the case would seem to make it an unlikely candidate for such a significant decision. Many geologists were shocked by the facts of this case, because the ancient slide complex was too large for Adamson to reasonably stabilize, and mistakenly believe that the decision declared Adamson's negligence. Although it was a major legal decision, its only effect on this particular case was to specify the rules for a second trial. The end result of Sprecher, as with Keys, supports what most of us interpret as the facts of the case. The case never even went to trial on the second round. It was settled for $10,000, which was a token compared to what the additional trial costs would have been. The willingness to settle for such a small amount suggests that both parties expected Adamson to prevail had it been taken to trial.

This decision has been widely criticized, primarily because of the faulty analogy the Supreme Court drew between decaying trees and landslides (e.g., Slosson, 1983; Burcham, 1983). Such reasoning has not been followed by other states. Still, it is a significant part of the recent trend toward discarding old common law rules in favor of the negligence idea of "reasonable care," an idea increasingly promoted by trial attorneys who are working for imperiled plaintiffs.

REALTORS: EASTON V. STRASSBURGER

Easton

v. Strassburger (152 Cal.App.3d 90, 1984)

was a California Appellate Court decision that expanded the duty of realtors

and the grounds for realtor negligence in selling faulty homes. The State

Supreme Court declined to hear the case, which gives it the force of law in

the state.

Easton

v. Strassburger (152 Cal.App.3d 90, 1984)

was a California Appellate Court decision that expanded the duty of realtors

and the grounds for realtor negligence in selling faulty homes. The State

Supreme Court declined to hear the case, which gives it the force of law in

the state.

The Strassburgers owned a home and adjacent property in Diablo, an exclusive area of Contra Costa County. It would appear that the home was originally constructed on a combination cut-fill pad without benefit of sufficient keying and benching of said fill. The fill experienced a minor slide in 1973 adjacent to the house, followed by a major slide of the same area in 1975. When the Strassburgers sold the property in 1976 to Easton, they did not disclose the slides or their subsequent "repairs." Soon after purchasing the home, there were additional slides and settlement in the fill which occurred in 1976, 1977, and 1978. Easton filed suit against the Strassburgers, the contractors, the realtors, and three other parties. The trial court found all the defendants negligent and apportioned 65 percent to the Strassburgers and 5 percent to the realtors. The realtors' appeal of that decision is the basis of this case.

The appellate court upheld the decision against the realtors, who were deceived by the Strassburgers just as Easton was. The court held, however, that realtors, as licensed professionals, have a duty to not only disclose what they know, but also what they, as professionals, should know, making "reasonable use" of their knowledge, skills, and experience. In the court's eyes, the realtors saw and ignored "red flags" (such as the mere presence of fill, uneven floors, and erosion netting placed on slopes) that should have alerted them, as experienced realtors, to potential problems. The court held that realtors have an affirmative duty to further investigate such obvious signs of distress.

The Easton case has spawned a whole new procedure for disclosure in California home sales. The California Association of Realtors developed disclosure forms to verify that the sellers have fully notified buyers of all defects, hopefully reducing the exposure of realtors to litigation. These disclosure forms have since been legislated into state law. An ironic footnote to this case is that the current owners of this property, which is still experiencing slope movement problems, were unaware of its history when they purchased it.

CONCLUSIONS

In summary, the concept of "reasonable care" has become more important in earth movement and surface water cases as the grounds for negligence have increased. The determination of what is reasonable is for a jury to decide, based largely on often contradictory expert testimony.

The vagueness of the law in this area creates a difficult situation for geologists and engineers. There is little guidance from the courts as to what constitutes reasonable care. However, it is not a question of law, to be determined by a judge, but a question of fact, decided by a jury. The legal trends actually make geologic sense. They promote case-by-case review and say that there are no absolute rules; it is also true of natural hillsides and streams. But, despite the earth's lack of homogeneity, we do need common standards and guidelines for each actor. The current legal climate creates an opportunity for geologists to educate attorneys, property owners, realtors, and ourselves: What warning signs indicate problems? What is "reasonable care" for hillside property owners? What are reasonable maintenance and landscaping practices? What constitutes a reasonable site investigation?

Geologists should consider these questions and begin publishing guidelines. Such professionally-accepted standards would carry a great deal of weight in expert testimony, and would help to define for juries what the state of knowledge and standards of profession are. Rather than complain about legal trends, this is a chance for the profession to take action and clarify some questions for ourselves, the courts, and the public.

REFERENCES

Burcham, 1983, Sprecher v. Adamson Companies: Nonfeasance immunity slides by the California Supreme Court: Loyola Los Angeles Law Review, v. 16, p. 625.

Ganong, J., 1986, Personal communication.

Kinyon and McClure, 1940, Interferences with surface waters: Minnesota Law Review, v. 24, p. 891.

Noel, D.W., 1943, Nuisances from land in its natural condition: Harvard Law Review, v. 56, p. 772.

Olshansky, R.B. and Rogers, J.D., 1987, Unstable Ground: Landslide Policy in the United States, Ecology Law Quarterly, v.13, n.4, pp 939-1006.

R.B., 1989, Landslide Hazard Reduction: A need for greater government involvement, Zoning and Planning Law Report, v.12, n.3, March.

Olshansky, R.B., 1990, Landslide Hazard in the United States: Case Studies in Planning and Policy Development, Garland Publishing Inc., New York, 176 p.

Slosson, J., 1983, Sprecher v. Adamson Companies: A critique of the Supreme Court decision: Real Property Law Reporter, v. 6, pp.117-120.

Tank, R.W., 1983, Legal aspects of geology. New York: Plenum Press.

Questions or comments on this page?

E-mail Dr. J David Rogers at rogersda@umr.edu.

![]()