|

One of our P-3Bs overflying the Admiral Ushakov, the lead unit of four

nuclear-powered 24,500 ton Kirov class battlecruisers completed by the

Soviets between 1980 and 1996. Our four Iowa class battleships

were taken out of mothballs, modernized, and recommissioned between

1982 and 1988 in response to these behemoths.

Aerial oblique view of the New Jersey firing three of her 16 inch guns

(one from each turret) simultaneously, after being recommissioned for

an unprecedented fourth time in December 1982. Every Naval officer

wanted to get a closer look at the old battleships. I was fortunate

to have actually gotten aboard the Missouri for a short stint.

The business end of the Iowa firing three of her 16-inch rifles at targets

in a firepower demonstration for visiting dignitaries from Guatemala

in August 1984. As I recall, the Iowa had been dispatched to Guatemala

to render medical and dental assistance. Simultaneous firings

did so much vibration damage to the computers aboard ship, they began

firing one rifle at a time, with some interval between.

This view shows the New Jersey firing a Tomahawk cruise missile.

The Iowa class battleships were reconfigured to carry 32 Tomahawk and

16 Harpoon missiles, as well as four Phalanx CWIS gatling guns.

Three of four were decommissioned in the fall of 1991, following the

first Gulf War. The Missouri was retained for a few more months with

a reduced crew so she could attend the 50th anniversary of the Pearl

Harbor attack ceremonies in December 1991. The Missouri had hosted the

Japanese surrender in Sagami Bay near Tokyo on September 2, 1945.

I am the officer in the leather flight jacket on the bridge of the USS

Missouri while the crew mans the rails as we depart San Francisco Bay

following the ship’s first port call in July 1987. The Missouri's

coning tower armor was 17 inches thick, making it pleasantly cool inside

during most days at sea. The belt armor protecting the hull was

over 12 inches thick and inclined at 19 degrees from vertical, to protect

the ships from armor piercing shells.

Propulsion on an Iowa Class battleship, as revealed in drydock. The

five-bladed inboard screws were 17 feet in diameter while the 4 bladed

wing screws were 18’-3” in diameter. The design power

output was 212,000 shaft horsepower (shp), with a 20% overload (up to

254,000 shp). During the New Jersey’s sea trials in December

1943 the engine room generated 221,000 shp, clocking 31.9 kts with a

displacement of 56,928 tons. The Iowas were the fastest battleships

ever built, by a wide margin. Their design speed was about 33.5

kts (38 mph), but a lightly loaded hull (51,000 tons) would have been

capable of achieving 35.4 kts (40.25 mph). That's fast enough

for waterskiing!

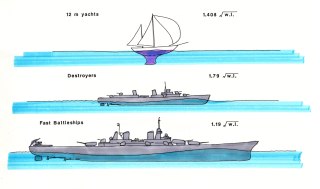

The Need for Speed. My sketch depicting the equations used to

determine the optimal waterline length for maximum speed, presenting

examples for 12 meter racing yachts (used in the America Cup races)

and World War II era destroyers and cruisers/battleships. These

values were empirically derived from model hull studies at the David

Taylor Ship Basin in Cabin John, MD in the 1930s and 40s. The length-to-beam

ratio for the Iowa Class battleships was 7.96.

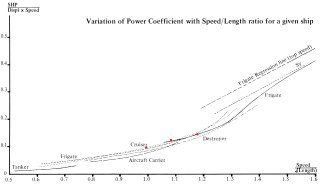

In the post World War II-era naval architects established a hydrodynamic

order or merit that eliminated the effect of displacement. The most

common comparison was this graph comparing the "power coefficient"

(shaft horsepower divided by the displacement and multiplied by the

speed) against the speed divided by the square root of length ratio.

The red dots are measured data for Iowa Class battleship sea trials. Note how these plot very close

to the line shown for cruiser hulls.

The width of the Iowa Class battleships was limited by the dimensions

of the Panama Canal locks. The maximum beam that could transit

the Canal was 108-1/6 feet because the locks are 110 feet wide. This

beam dimension was then multiplied by 7.96 to determine the waterline

length of 860 feet. This shows the battleship Iowa transiting

the Pedro Miguel Locks on June 6, 1984. Looks like a tight fit!

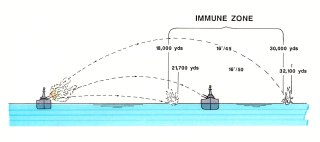

The Iowa Class battleships were designed to be immune from 18-inch armor

piercing naval gunfire at ranges between 18,000 and 30,000 yards.

Below 18,000 yards the lower trajectories of incoming shells could conceivably

pierce the inclined hull armor package.

Nice shot of the Missouri positioning herself for underway refueling

from the USS Kawishiwi (AO-146), a Neosho class tanker. The carrier

Kitty Hawk is in the background, waiting her turn. This was taken

on June 25, 1986, shortly after the Missouri was recommissioned in San

Francisco (her intended homeport).

Underway replenishment between the Missouri and the stores ship USS

Sylvania (FS 2), the second unit of the Mars Class ( 576 feet long with

a displacement of 17,500 tons). The US Navy is designed for global

mobility and sustained periods at sea. This mobility is sustained

by a "invisible" fleet of stores ships and oilers that replenish

the warships every few days.

The Iowa Class battleships were the smoothest riding ships I ever rode

on, even in rough seas. This shows the forecastle of the Missouri

breaking some large waves, as viewed from the O-6 level on the bridge,

358 feet behind the bow.

View from the O-4 level of the bridge as the 16-inch/50 caliber Mk 7

rifles of turrets one and two on Iowa are fired simultaneously.

Ear protection was essential, but no matter how much you braced yourself,

you always winced at the concussion of so much cordite detonating.

Another view taken from higher on the bridge of two other 16-inch rifles

firing on turrets 1 and 2. These are capable of hurling projectiles

weighing between 1900 and 2700 pounds 21 to 23 miles across the sea!

I am standing inside Turret No. 2 on the USS Missouri. The round tube

at left is the old optical (mirror) range finder, retained as a hand-operated

back-up in case the radar ever failed.

Breech of 16-inch/50 caliber rifle on the Missouri. The caliber

identifies the length of the barrel: a 50 caliber gun with a 16 inch

bore would give a barrel length of 50 times 16 inches, or 800 inches

(66.6 feet). The longer the barrel, the more accurate the trajectory

of the projectiles. The largest of the previous American battleships

had employed somewhat shorter 16-inch/45 caliber rifles.

Shipboard drill using OBA’s, or Oxygen Breathing Apparatus. Every

member of the ship's crew must complete fire fighting school and know

their duties and responsibilities for different kinds of threat conditions,

such as battle stations or fire aboard ship.

Stern view of the Missouri firing at Iraqi targets in Kuwait during

Operation Desert Storm

Turrets 1 and 2 firing simultaneously. Note the 16 inch projectile just

emerging from the barrel of the closest rifle! This was taken

from the forecastle (foc’sul) looking aft.

Questions

or comments on this page?

E-mail Dr. J David Rogers at rogersda@mst.edu.

|