SCIENCE VERSUS ADVOCACY:

The Reviewer's Role to Protect the Public Interest

J. David Rogers 1

and Robert B. Olshansky 2

1 UM-Rolla Dept. of Geological Engineering

129 McNutt Hall, 1870 Miner Circle, Rolla, MO 65409

2 Dept. of Urban and Regional Planning, University

of Illinois,

Urbana 907 1/2 W. Nevada St., Urbana, IL 61801

INTRODUCTION

In California, the Alquist-Priolo (A-P) Special Studies Act, enacted in 1972,

requires a study by a registered geologist for any development proposed within

a State-designated "active" fault zone. Prior to the bill's passage,

the State Mining and Geology Board (SMGB) had adopted a policy which requires

local jurisdictions to review fault studies for adequacy (Section 3603e of

Policies and Criteria of the SMGB, in Hart, 1990). Soon afterward, the A-P

Act was approved, but it does not contain any requirement for external review

of geology reports. Local municipalities must provide for peer review to be

in accord with SMGB P&C section 3603e, but have a free reign to pick who

should provide such services. These agencies are free to request a review

from the State Division of Mines and Geology (CDMG), but are neither bound

to make such requests, nor abide by the review. Nor are local agencies obliged

to honor the State's on-going interpretations of surface fault rupture. In

cases where development precedes A-P zoning, special studies are not required

and new structures may be built directly upon active and potentially active

faults. Several recent examples of this situation would be the Simi-Las Posas

and Malibu Coast faults.

Under the precepts of the Alquist-Priolo Act, before lots can be subdivided within a designated Special Studies Zone, a registered geologist must perform evaluations of surface fault rupture hazard within that zone. If a developer's geologist is "unable" to expose evidence of recent faulting, should this lack of evidence be used to support the premise that "no faults exist" on the site? What if such a suggestion is made along one of the major, regional faults, recognized by the entirety of the scientific community'? In California, down-zoning of faults from "active" or "potentially active" to some more-benign classification carries with it significant land use implications. Might some geologists be tempted to tilt their findings, in deference to client pressure? One example of fault down-zoning that drew considerable attention is presented herein.

The authors conclude that State law should be amended

to provide consistency in external review of Special Studies Zone reports

by requiring that the CDMG be charged with making mandatory reviews of all

reports. In those instances where local agencies already maintain full-time

review geologists, the CDMG review would be more cursory, in order to provide

an overall acceptance that would not be tainted by local developer influence.

Should professional disputes arise, these should be arbitrated under an appeals

process similar to the system employed by Los Angeles and Orange Counties,

as well as the City of Los Angeles.

Alquist-Priolo Special Studies

Zone Act of 1972

In the wake of the February 1971 San Fernando earthquake near Los Angeles,

California enacted legislation (Alquist and Priolo, 1972) to protect its residents

from damage caused by surface fault rupture. All forms of surface ground rupture

only account for about 1% of the total property damage in any given quake

(99% of the property damage being ascribable to ground shaking and other forms

of ground failure), such requirements seemed a logical response for politicians

hungry to be perceived as "doing something" about earthquake safety

(Slosson, 1974; Slosson and Keaton, 1992). In addition, such legislation cost

the State very little, creating 3 geologist and a geologic aide positions

within the State Division of Mines and Geology to be charged with cataloging

the reports and periodically updating surface fault rupture maps on overlays

of standard U.S.G.S. 7.5-minute quadrangles (a fourth geologist position was

added in 1985). Special Studies "Zones were defined as a strip of land,

about 1/4 mile wide, bracketing the presumed surface traces of the State's

"Reprint from Proceedings of the 35th annual Meeting of the Association

of Engineering Geologists(1992), Long Beach, CA., p. 371-378."most recently

active faults. The Act did not state that faults not yet zoned would constitute

a hazard.

Originally enacted under the aegis of State Geologist Wesley G. Bruer, the draft Act called for mandatory review of the adequacy of such studies by the CDMG. From its initial introduction, the Act was heavily opposed by California's influential real estate lobby, who were suspicious of its potential effects on real property values within proximity of fault zones (Slosson and Keaton,1992). Prior to passage of the Act, there had been no such limitation on development in California. Throughout the 1960's, subdivisions had been constructed along the 1906 surface rupture of the San Andreas fault in Pacifica, South San Francisco and San Bruno. Real estate interests were also opposed to the Act's calling for disclosure of whether a property is located within a Special Studies Zone. The Act makes no provision for informing a buyer or seller of the exact location of their parcel with respect to the mapped traces of any fault, but it did charge each City with the preparation of a Seismic Safety Element that would include all A-P Zone data.

In the first full year of enactment, CDMG mapped the State's four largest faults, the San Andreas, San Jacinto, Calaveras and Hayward, issuing 175 maps in July 1974. One and a half years later, about a dozen additional faults were zoned on another 76 maps, while five of the original maps were revised. In the initial batch of maps issued in 1974 and 1976, faults of Quaternary age were shown as "potentially active". A-P maps issued after that were amended to include only those faults thought to be "sufficiently active," or of Holocene age (Hart, 1986).

That same year (1976) saw the CDMG initiate its "10 Region Program," by which all parts of the State were to be analyzed for evidence of Holocene faulting. This program was completed in late 1991, thereby capping the initial phases of the A-P Act, which took 18 years to implement.

Since 1976, the State has also compiled Fault Evaluation

Reports, or FERS, which document the rationale for zoning. The most active

faults were evaluated initially, with lessor known segments being evaluated

as time and budget allows (Hart, 1990). In some cases, zones that had originally

been mapped as faults based on structural lineaments, such as the Antioch

and Pleasanton faults, have been withdrawn from A-P zones due to the lack

of evidence for Holocene surface rupture.

Guidelines for Practice

In 1973, the new State Geologist, Jim Slosson, introduced the first of a series

of "Guidelines for Practice," one of which (CDMG Notes Number 37)

dealt specifically with what subjects, methods of investigation, and conclusions/recommendations

should be included in A-P Zone investigations. The other Guideline Notes were

issued in 1975. In October 1975, Note 49 was issued. It dealt specifically

with evaluation of surface fault rupture (and is still included in Appendix

D of CDMG SP 42). The Guidelines were adopted by the SMGB in 1978. In 1986,

the State Board of Registration for Geologists and Geophysicists rescinded

such guidelines after they had been used as a de facto form of standard-of-care

in a lawsuit against a prominent southern California geotechnical firm. This

lawsuit also involved the Association of Engineering Geologists, who had published

Slosson's (1984) article on the CDMG Guidelines, noting that they had originally

been drafted by the southern California Section of AEG. At the time (1986),

the Board of Registration for Geologists and Geophysicists felt such action

was warranted in the interest of limiting professional liability.

Having been published, these guidelines are still being utilized in some areas,

even though the State Board of Registration provides no official sanction

of them. The membership of AEG needs to consider the value of endorsement

versus the supposed reduction in risk from lawsuits being brought against

them.

Proposition 13

In 1978, tax reform advocates Howard Jarvis and Paul Gann spearheaded a public

movement spawned by escalating property assessments that was caused by market

factors and spiraling inflation. At the time, the State treasury enjoyed a

$1 to $2 billion revenue surplus, collected mostly from income taxes. For

the common property owner, the rapid inflation in property values meant dramatically

increased property taxes, but no financial windfall until their property was

sold. For those who were retired, on fixed incomes, or who had paid off their

homes and had no intention of moving, the burden was extreme. The Act passed

by a wide margin, despite pleas from politicians that the bill's fallout would

eventually bankrupt the State, local municipalities and school districts.

City and County government suddenly found themselves with one-third the available

funds that they had enjoyed prior to the Proposition's enactment. Local municipalities,

so dependent on property tax monies, suddenly found themselves groping for

alternative sources of revenue. They soon discovered a suitable loophole,

that of "developer fees," which collected at the outset of building,

could not be construed as 'Taxes". The California courts subsequently

agreed with this interpretation.

Evolution of Increased Developer Influence

As a consequence of these newly-conceived "developer

fees," construction activity suddenly bore the burden of supporting local

government. Because of this, developers came to wield significant financial

influence on local politicians. City administrators also quickly realized

that their jobs depended on developer fees. By promoting various forms of

fee-taking, such as residential construction, shopping centers, business parks,

hotels or landfills, local jurisdictions, such as cities and counties who

had review powers over development could make-up the Prop 13 shortfall. Special

districts and schools who were previously funded by property taxes, but who

were incapable of exercising any substantive review power over commerce, found

themselves lacking for funds. Since 1987, California school districts have

been allowed to charge $1.65 per square foot of new residential construction

(new structures or additions) and $0.27 per square foot for commercial/industrial

construction.

Shopping for Consultants

Given the enormous financial and political factors governing the subdivision

of unimproved land, many developers will shop around for consultants who they

perceive to be "reasonable," either by way of cost, or in the manner

by which they are swayed by the developer's wishes. In California, it is not

uncommon for developers of geologically hazardous parcels to consult with

a half dozen consultants before settling on one with whom they feel "comfortable".

Main-line geotechnical firms and senior engineering geologic consultants usually

steer clear of working for developers of tainted hillside properties, because

their experience has shown the risk of incurring liability in such work (Olshansky

and Rogers, 1987). In many cases, it is the less-experienced consultant that

accepts an engagement, oftentimes oblivious to the severity of geologic hazards

present on a site.

Without clear guidelines for preparation of Alquist-Priolo (A-P) Zone reports, many developers will make it clear that they desire the minimum possible effort to be expended in "checking off the fault study box" of their development application. A-P Zone reports, by their very nature, require extensive library research, delving into the past work of other geologists within the subject fault zone. From the outset, the cost of such preparatory work may be extensive, in comparison to the normal type of site-specific geologic investigations.

A-P Zone reports should include a thorough review of

all previous data collected on the fault in question. This data should be

culled from the CDMG Fault Evaluation Reports, A-P Zone Maps and their appurtenant

references, academic sources, and a thorough compilation of previous A-P reports.

A-P studies require research of an academic quality. Such studies must recognize

past work, and either accept or refute their conclusions with convincing evidence.

Unfortunately, a sizable portion of the profession never look beyond the limits

of their client's property, nor do they use the library. When failures do

occur, these same geologists commonly utilize a "standard-of-care"

defense, stating that they don't do any less than others providing similar

services in the same area (Slosson, Shlemon and Slosson, 1992). In these cases,

juries must determine whether or not the professional exercised "reasonable

care" in performing their duties (Olshansky and Rogers, 1992).

Impartiality and Professional

Qualifications of the Reviewer

Section 3603e of the Policies and Criteria of the SMGB requires that a registered

geologist shall evaluate geologic reports required by state law and report

the results to CDMG. This makes sense. Geology is not a precise science, and

the field advances by means of consensus decisions.

Because geology lacks definite "answers," it is particularly subject to abuse in the high-pressure world of land development (Olshansky, 1991). It probably goes without saying that, in order to maintain credibility and achieve effectiveness, a reviewer of geologic reports should be of the utmost professional calibre, suitably educated, experienced and registered in the field being reviewed. The SMGB criteria makes no allowance for non-registered individuals, such as federally employed scientists or university professors who are not registered (for example, the Town of Portola Valley originally engaged the services of Stanford Geology Professor Arvid Johnson to be their part-time'Town Geologist"). Those agencies who have employed non-registered individuals in a review role have usually received complaints from those being reviewed. Unfortunately, with the demise of public agency funding, many registered geologists have been drained from the public ranks.

It is important that a reviewer not, in any way, be within the influence of a development applicant; through work for them in another area. Nor would it be advisable for the reviewer to perform private consultations within the jurisdiction of review. To do so might be construed as a conflict of interest. Since the passage of Proposition 13, local agency employees have been perceived to be increasingly influenced by developers, through their elected officials and special "consultants," hired by developers to pave the permitting process through their local experience, or connections.

In some areas, such as San Diego, local consultants

"take turns" reviewing each others' work. Such a policy is often

enacted to expel the notion that a local agency "plays favorites"

in terms of retaining a particular consultant. However, such a system is fraught

with other inequities. These include a non-uniform review process, using consultant

staffs which may not be aware of area history and performance, and the temptation

for the consultants to be easy on one another, for fear that their own reports

will be subject to scrutiny at a later date. In such a situation, professionals

begin to resemble a guild, the members of which are only concerned with their

own financial success.

Case History of a Disappearing

Fault

Is it really possible for a developer to "buy" a professional geologic opinion that would be favorable to their development application? Many experienced reviewers believe that it is (Slosson and Keaton, 1992). One of the more notorious cases, which gave rise to a recent reassessment of the State's Board of Registration for Geologists, is briefly profiled below. It serves to illustrate the contrast between professional disagreement with that of one individual taking a position counter to the entirety of the geologic community.

The case involved a 1988 development application for 80 lots on a 258-acre parcel astride the Calaveras fault, adjacent to the upscale Castlewood Country Club in Pleasanton, California. In 1861 , the Calaveras had spawned a M. 6.1 to 6.9 earthquake, leaving a semi-continuous ground fissure, 6 to 8 miles long, according to local news reports of the event. This fissure extended south to within a mile of the applicant's site. Early workers had mapped the fault out in the floor of the valley, a location shown in the original (1974) A-P Zone map. But every worker since the early 1970's had placed the fault further up the valley slope, at the foot of Pleasanton Ridge, which is comprised of Great Valley Sequence rocks (Dibblee's Panoche formation).

Mapping for geology dissertations in 1972, 1974, 1978, and 1979 had all shown the fault on the upper slope, as had USGS (1978 and 1980) and State (1 981) studies. But this work also suggested that the fault's surface trace was obscured by a complex of coalescing late-Pleistocene and Holocene landslides, which had previously been identified in a series of Federal studies (1973, 1974, 1975 and 1978). The CDMG's A-P Zone map was updated in 1982 to reflect the shift in thought. In the 15 years prior to the development application, the parcel was one of the most intensively studied sites in the San Francisco Bay region.

In 1984, a local consultant had been retained to perform an A-P Zone study of the site. Finding the fault's surface trace hard to track through the landslide deposits, they had drilled deep holes to see what bedrock units lay beneath and thereby, hopefully, be better able to localize the main trace of the fault. In this area, the fault truncates Cretaceous-age Panoche strata against late Miocene-age Briones sandstone member of the Monterey formation. This earlier consultant also utilized electric logs from nearby water wells, which penetrate Pleistocene-age gravels that infill the down-dropped, eastern escarpment of the fault beneath the Amador Valley.

Apparently uncomfortable with the 1984 report, the same "development consultant," a registered civil engineer, turned to another firm in 1988. This new consultant began anew, excavating almost 2300 lineal feet of shallow trenches across the site and came to dramatically different conclusions: he reported no evidence of either landsliding nor surface fault rupture across the site. Such a finding had enormous financial implications, in as much as a maximum number of lots could be developed if no setback were required from a fault. In addition, by excluding any mention of "faults" or "landslides," the property would be less tainted.

In justifying their departure from the status quo, the new consultant argued that the Calaveras fault did not extend through his client's property: it either lay to the east (out in the valley), or began anew, as a form of "step-over," to the north of his client's parcel. In August 1988, the Pleasanton Planning Department stated that the report met the requirements of the A-P Act and suggested that the City request evaluation and advice from CDMG. In September, ,the City then wrote a letter to CDMG requesting a review of the new report and to meet with them. In October, the CDMG's senior geologist responsible for coordinating A-P Zones met with the City and informed them that he felt the report was inadequate and that it neither proved the absence of an active fault nor the absence of landsliding. He went on to recommend that additional trenching be employed at the site.

The news that an active, 180 km long fault was suddenly discovered to stop just south of, then continue, just north of, a particular client's parcel, was in stark contrast with all earlier reports and studies, but not impossible. The conclusions were greeted with an ample degree of skepticism by the authors, who were under contract at the time as the City's geotechnical reviewer for the Public Works Department. Public Works had been asked to comment on the geotechnical and geologic reports by the Planning Department, under whose aegis the application was being processed.

The City's geotechnical reviewer took the new findings to task on a number of issues, including: citing the omission of all but 1 of the post-1970 academic references which uniformly disagreed with the new interpretation; the almost casual rejection of the earlier geologic report, which had concluded that, based on deep bedrock borings and geophysics, both landslides and fault were present on the site. The conclusion that no landslides existed on the site was in direct disagreement with every published and academic reference dating back to 1973 and that just because the consultant could not find the fault in shallow trenches was insufficient scientific basis to thereby conclude that no fault exists.

The geotechnical reviewer's comments were not greeted warmly by the Planning Department, and the reviewer was banished from any further meetings or consultations on the project. Other consultants and academics affirmed the reviewer's concerns, citing the fundamental premise of intermittent outcrops in field geology has never been interpreted to thereby mean that units do not exist where they cannot be seen. Others, more well-versed in seismotectonics, wrote local newspapers expounding the kinematic impossibility of a crystal-sized feature, like the Calaveras, stopping and starting anew without exhibiting some form of fault termination feature.

The city felt secure in its position, citing the fact that it had continued to employ the same geology reviewer both before and after the controversy, and that under State law, that was all that was required (Slosson and Keaton, 1992). Meanwhile, the City's geotechnical consultant was fired for making the criticisms which were in agreement with those of CDMG.

On two occasions, the applicant excavated additional trenches. The first was in December 1988, although some of the trenches were closed while others were filled with water. Some interested parties were invited to the site, but none that had been critical of the consultant's findings in the previous months. CDMG's senior geologist reviewed these trenches and again stated that there was no evidence to support the absence of a fault. Later that month, the CDMG geologist wrote up his concerns, again suggesting additional trenching. This second set of additional trenches were subsequently excavated later that winter, but this time the CDMG senior geologist was not invited to make an on-site inspection. After this final set of "additional trenches" were completed, the consultant issued his final report, again reiterating that neither fault nor landslides existed on the site.

In this last chapter of the field work, the Planning Department's review geologist was the only external person ever able to review the trenches first-hand. An eminent soil pedologist was brought in as a consultant for the developer to date the soils exposed in the trenches, and concluded that this was a site with "dramatic sedimentation rates." The project's detractors responded that "rapid sedimentation rate" to the pedologist translated to "active debris flow/earthflow accumulation" to engineering geologists.

Despite all the controversy, the City approved the application, accepting the omission of the Calaveras fault across the applicant's parcel, citing the concurrence of the reviewing geologist working for the Planning Department. Unconvinced, the CDMG's Senior Geologist responsible for coordinating Alquist-Priolo Zone mapping refused to alter the CDMG interpretation of the area. The applicant's geologist cried foul, citing "professional jealousy" and his perception as to a lack of open minds to "new interpretations."

A number of local consulting geologists familiar with the City's application processes repeatedly demanded in open letters to the media that the City employ the U.S.G.S. to make an independent review of the "new hypothesis". The U.S.G.S. even wrote to the City, offering its services. The City consistently refused to take any such action. Others who had studied the same area argued that, if the consultant were serious in perfecting a new paradigm for the Calaveras fault, he should have invited everyone to come and view the trenches themselves, as is a common practice among Bay Area geologists.

In the end, the City maintained that it had done everything

required by statute, and that it was not bound to be in agreement with the

CDMG, USGS, or anyone else. They maintained that they had provided outside

professional peer review and that such review had been in agreement with the

developer's consultant, in so much as the surface trace of the fault could

not be found. However, the Planning Department's review geologist stopped

short of endorsing the consultant's theories that "no fault exists on

the site".

Fallout from the Calaveras

Controversy

As letters to the editors of local papers continued to stream in, investigative

reporters continued to explore the case, eventually unveiling a three-day

expose on the issue of competency of engineering geologists which appeared

in the Oakland Tribune in June 1990 (Newbergh and Grabowicz, 1990), receiving

national exposure. The State Assembly reacted to strong criticisms of professional

incompetence levied by a former State Geologist and the Head of the State

Seismic Safety Commission in the articles. One of the articles' most stinging

accusations involved the State Board of Registration, which was characterized

as an entity that had never exercised disciplinary action against registered

geologists in its 20-year history. The Board's Executive Director retired

and the Board's role in protecting consumers and restricting licensure is

currently being reevaluated by order of the legislature.

Handling Professional Disputes

Many geologists were upset and embarrassed at the public

exposure of what they viewed as professional differences aired in the Tribune

articles. These individuals saw this as petty squabbling which could only

diminish the credibility of geologists in the public eye. To others more closely

affiliated with the case, it was simply the inevitable result of professional

advocacy taken too far in the post-Proposition 13 era. To these geologists,

it wasn't a case of one geologist versus another, but of an entire profession

and body of knowledge lined up against one maverick.

Was the maverick subjected to undue harshness? On the local level his unique

views prevailed, and he was paid handsomely for his efforts. His detractors,

who worked so hard to dissuade him, received no compensation. In fact, the

City reviewer who had disagreed was fired: this rather thoughtless action

on the part of the City was probably the smoldering fuse which eventually

caused so many fellow geologists to become embroiled in the controversy. The

projects' critics argued in the media that the maverick was not a scientist,

but an advocate for his clients. They cited his lack of serious publishing

and consistent secrecy in logging trenches as actions abnormal to good science.

They argued that individuals suggesting new theories of seismotectonics have

never been taken seriously unless they openly share their work out in the

field, where critical interpretations are made.

Bay Area engineering geologists acted again about a year later when the Santa Clara County Board of Supervisors attempted to fire the County Geologist; who although perceived by most as a maverick, was staunchly supported by the consulting geologic community: most respect his many years of effort and were sympathetic to the frustrations that come with his position. If not for the public outcry of his peers, this individual would have had to resort to the Courts to retain his job.

It is inevitable that all of us are subject to some scrutiny and criticism from our working peers. The academic world is full of professional jealousy; however, over the centuries, scientists have gradually developed a system of mutual peer review which is designed to check the mavericks and remove the charlatans that may sift into the system. This peer review is in the form of constant review of one's work by fellow academics. People who do not submit their research efforts to tireless scientific scrutiny generally are not seen as authorities and, when they propose a novel theory, its validity may be seriously questioned.

Though such a system may seem harsh, it has worked with remarkable clairvoyance in the past half century. Consider the incredible postulate by Walter Alvarez at U.C. Berkeley in 1977 that an iridium-rich clay existed world-wide at the Cretaceous-Tertiary boundary, 63 million years ago. This revolutionary discovery withstood peer review because Alvarez had performed a thorough workup at six widely dispersed sites, knowing the scrutiny to which such a premise would be measured. Skeptics were free to take their own look at the K-T boundary, and many did, thereby becoming believers.

Contrasting the above example of good science would be the sensational case of Dr. Iben Browning, a climatologist turned earthquake predictor. In December 1989, this man nurtured a media frenzy of sensationalism and worry about his prediction of a massive quake at New Madrid, Missouri, the scene of the country's largest quakes in 1811-12. Despite the lack of appropriate credentials, Browning was able to play on people's fears and public awareness following the Loma Prieta earthquake in California. Geologists and seismologists from across the country assailed Browning's accusations, which he colored as "professional jealousy", all the while selling his "earthquake prediction" package of unpublished articles for $500 per copy through the media.

Should fellow scientists have a means by which to censure a person like Browning? Most think that we should. If we employ no manner of discipline or warning, what is to prevent a truly incompetent individual from unknowingly putting the public at risk? Agents working for public entities must be cognizant of their public trust. The average person is depending on them to safeguard the greater, long-term welfare of the public at-large. Are we doing that if we buckle under to developer pressure while possibly turning a blind eye towards safety? Shouldn't we err on the side of conservatism and not on that of the developer, who owns a 10-year statute of limitation?

Geology, by its very nature, is probably one of the

most subjective sciences (Slosson, 1991). The individual training of our licensed

professionals extends from no college degree and no professional exam, all

the way up to the doctorate degree and completion of a rigorous professional

examination. This is in stark contrast to other professions, such as medicine

or law, where minimal levels of graduate education, professional training,

and examination are mandated. Add to this variance that of professional experience.

Most of a geologist's professional training is simply who they have worked

under, before they themselves, became registered. Herein lies another great

variable, one which the geologist registration act will provide for baseline

qualification by examination after all of the grandfathered practitioners

pass on.

CONCLUSION

The authors would maintain, therefore, that professional disputes

are inevitable within the practicing geologic sciences. Recognizing this fact,

we would strongly suggest that some manner of arbitrating disputes be mandated

as well as provision for appeal of disagreements, coupled with the requirement

for professional peer review. In the City of Los Angeles, the grading and

engineering geology sections of building inspection maintain advisory blue

ribbon panels comprised of recognized industry experts from consulting, academia

and public agencies. A minimal number of these individuals periodically convene

to hear and rule upon appeals involving matters of professional technical

disagreement. Each side is allowed to present its case before the panel and

is subjected to rigorous questioning. The decision of the panel is binding:

peer professionals rule on the case without the expenditure of time and funds

so common with legal battles. This type of system could be employed by every

local entity in California with nominations for panel members coming from

academic institutions, the USGS, CDMG and professional organizations like,

SSA, GSA, AEG, ASCE, ICBO, and APWA, NSPE, AIPG, ASFE and the CGEA (formerly

SAFEA).

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank the following individuals for their input

in the preparation of this paper: Earl E. Brabb, C. Michael Scullin, James

E. Slosson, Earl W. Hart, William R. Cotton, J. Ross Wagner, Marc W. Seeley,

Michael E. Perkins, Chris Wills, Sands H. Figuers, Patrick L Williams, George

0. Reid and Raymond P. Skinner. Earl Hart, Mike Scullin, James Slosson and

Robert Larson kindly reviewed the manuscript and provided helpful comments.

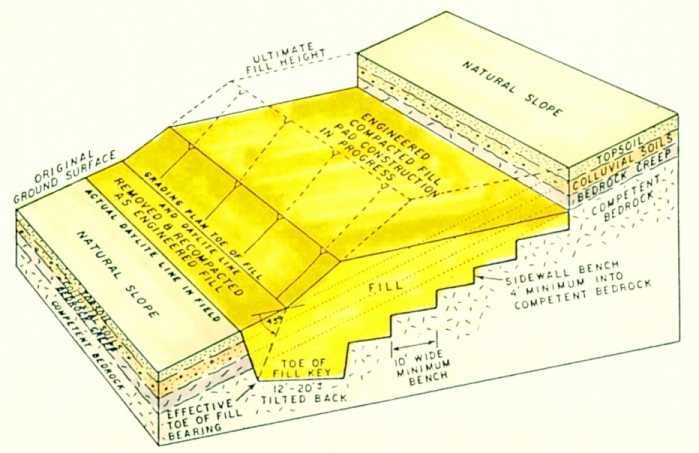

Recommended overexcavation for fill embankments developed

in Orange County in the late 1960s, and presented in

"Excavation and Grading Code Administration,

Inspection and Enforcement" by C. Michael Scullin (Prentice Hall, 1983).

Note that the toe-of-fill keyway should extend out in front of the embankment

face, and that excavation should

be taken through surficial soil deposits and the bedrock creep zone.

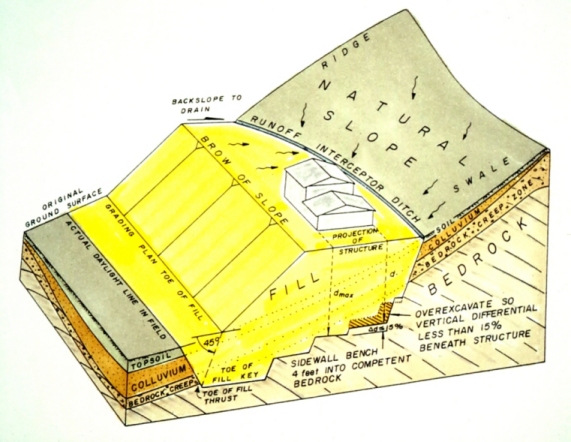

Recommended overexcavation for fill embankments supporting

structures, as presented in "Long Term Behavior of

Urban Fill Embankments" by J. D. Rogers in 1992 (in Stability and Performance

of Slopes and Embankments-II, American

Society of Civil Engineers Geotechnical Special Publication 31). This suggested

standard builds upon that of Scullin (1983)

by requiring additional overexcavation beneath structures to limit fill thickness

to 15% differential.

REFERENCES

Alquist, A., and Priolo, P., 1972, Alquist-Priolo Geologic Hazard

Zones Act: State of California Senate Bill SB 520 (enacted December 22, 1972,

effective from March 7, 1973): California Public Resources Code, Division

2, Chapter 7.5, (amended four times since initial adoption).

Hart, E. W., 1986, Zoning for Surface-Faulting Hazards in California: in Proceedings of Conference XXXII, Workshop on Future Directions in Evaluating Earthquake Hazards of Southern California: U.S. Geological Survey Open File Report 86-401: pp. 74-83.

Hart, E. W.9 1990, Fault-Rupture Hazard Zones in California:

California Division of Mines and Geology: Special Publication 42, 24 p.

Newbergh, C., and Grabowicz, P., 1990, Earthquake Hazards Covered Up (June 17, 1990), Area Builders Follow Maverick Geologist's Lead (June 18, 1990), and Critical Reports Put Geology Board on Shaky Ground (June 19,1990): Oakland Tribune, Oakland, California.

Olshansky, R.B., 1991, Use of Geologic Hazard Information

in Planning: Proceedings ACSPAESOP Joint International Congress, Oxford, UK,

1 1 p

Olshansky, R.B. and Rogers, J.D., 1987, Unstable Ground: Landslide Policy

in the United States:

Ecology Law Quarterly, v.13, n. 4, pp. 939-1006.

Olshansky, R.B. and Rogers, J.D., 1992, The Concept of 'Reasonable Care' on Unstable Hillslopes:

in Reviews in Engineering Geology IX: Landslides/landslide Mtiigation, J.A. Johnson and J.E. Slosson, ed.s, Geological Society of America, in press.

Slosson, J.E., 1974, Status of the Alquist-Priolo Act: letter from Slosson (State Geologist) to Senator Alquist: November 21, 1974v 2 p.

Slosson, J.E., 1984, Genesis and Evolution of Guidelines for Geologic Reports: Bulletin of the Association of Engineering Geologists, v. XXI, n. 3, pp. 295-316.

Slosson, J.E., 1991, Where are the Basics?: in Academic Preparation for Careers in Engineering Geology and Geological Engineering: Association of Engineering Geologists, Special Publication No. 2, pp. 13-17.

Slosson, J.E., Shlemon, R.J., and Slosson, T.L., 1992,

Standard of Practice Equates to an Ever-Evolving Number of Failures: Proceedings

35th Annual Meeting, Association of Engineering Geologists (this volume),

Long Beach.

Slosson, J.E., and Keaton, J.R., 1992, Fault Rupture Hazards, the Alquist-Priolo

Fault Hazard Act, and Siting Decisions in California: in Uniformity in Site

Selection, AEG Special Publication, in press.

Questions or comments on this page?

E-mail Dr. J David Rogers at rogersda@umr.edu.

![]()